The Chronic Miasms - Part One & Two

By Dr Will Taylor

Introduction by Editors:

Dr Will Taylor has written a six piece essay on The Chronic Miasms. It is a detailed analysis on the development and evolution of homeopathic miasms and how Samuel Hahnemann first developed his ideas and how that has been understood and evolved since within the profession. It is an excellent, detailed study of Hahnemann’s thinking and how this was understood and interpreted by future homeopaths. It explores such concepts as to whether miasms are only acquired infectious influences or also inherited dispositions and also whether there can be more than 3 miasms and how that can be rationalized. It also explores Hahnemann’s understanding of the roots of disease and what that means practically in prescribing for long standing chronic conditions. We hope that this exploration will further elucidate this fundamental part of homeopathic theory and practice. We are publishing two parts in each of the next three journals so these essays can be absorbed over some time. What follows is part one and part two.

Part One

The chronic miasms are one of the most misapprehended and misrepresented topics in homeopathic practice. On publishing in 1828 the first volume of his text The Chronic Diseases: Their Peculiar Nature and their Homeopathic Cure, Hahnemann wrote to his close colleagues Johann Ernst Stapf and Gustav Wilhelm Gross, (in Bradford, The Life and Letters of Dr Samuel Hahnemann):

” You and Gross are the only ones to whom I have revealed this matter. Just think what a start you have in advance of all the other physicians in the world. At least a year will elapse before the others get my book ; they will then require more than half a year to recover from the fright and astonishment at the monstrous, unheard of thing, perhaps another half year before they believe it, at all events before they provide themselves with the medicines, and they will not be able to get them properly unless they prepare them themselves.”

The timeline Hahnemann suggested could easily be stretched out at least 200 years. Hahnemann’s observations on the Chronic Disease remain one of the most misapprehended and misrepresented aspects of his teachings, and promise to be for some time.

We first need to understand what Hahnemann intended in his use of the term “miasm.” As a term not in common use in contemporary English, it’s far too easy to impose a range of proposed meanings and implications. We’ll encounter suggestions that the chronic miasms represent inherited predispositions responsible for chronic illness, “inherited imprints of disease predispositions,” “collective karmic patterns,” “epigenetic imprints,” “ancestral energetic layers,” “patterns of reaction,” "diatheses,” “energetic imprints,” “latent programs in the collective field,” “archetypal energy patterns,” “energy tendencies that create predispositions towards the manifestation of a certain disease in an individual,” “subtle energy fields,” & such; none of these are consistent with Hahnemann’s teachings.

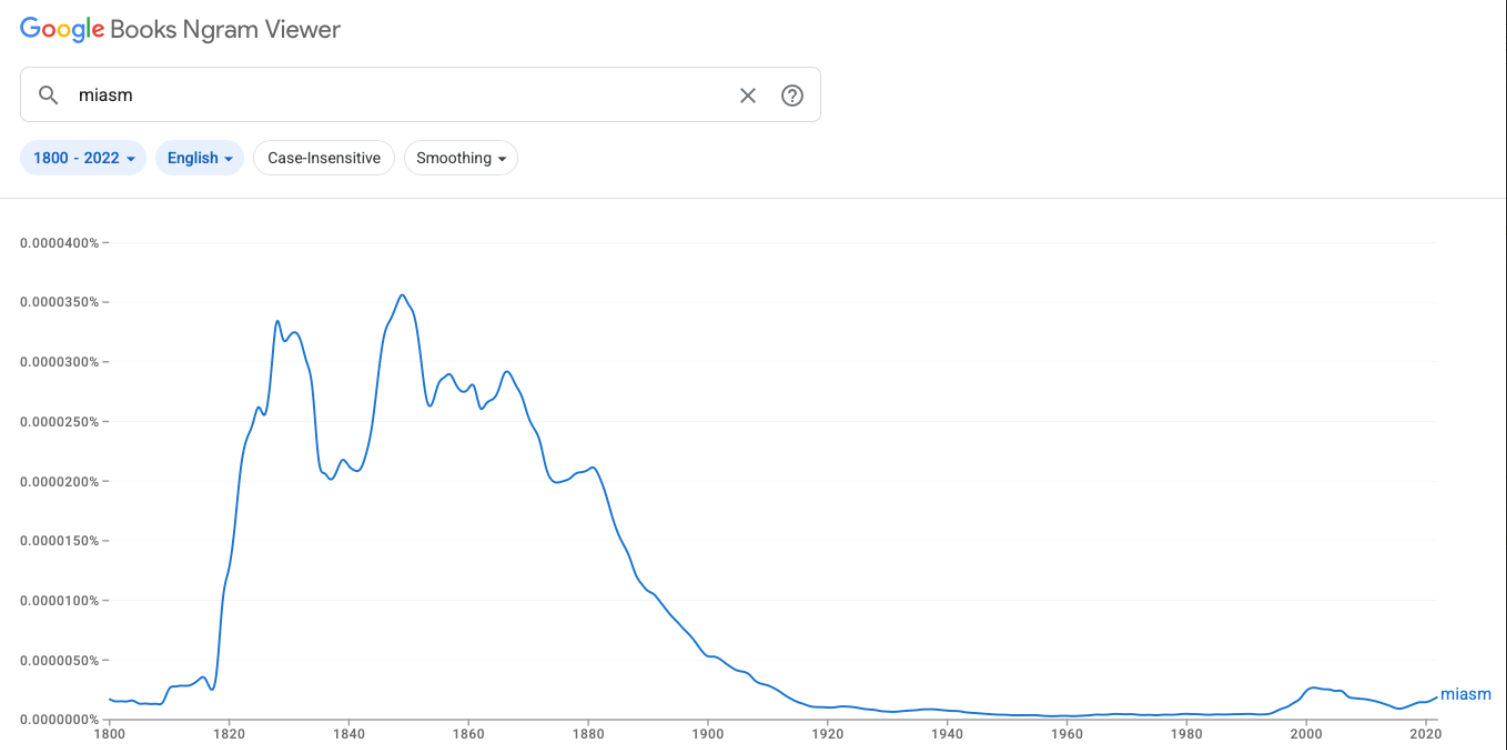

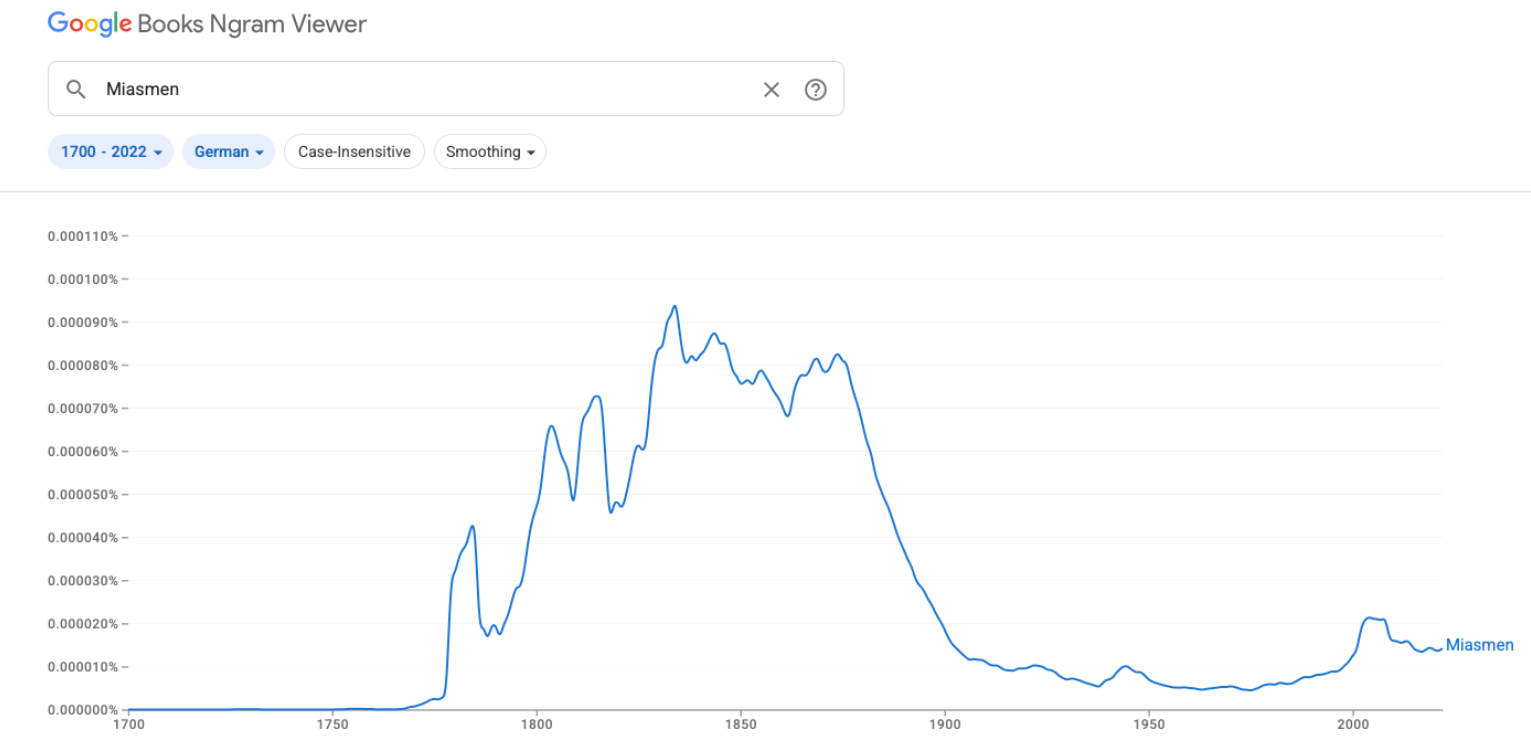

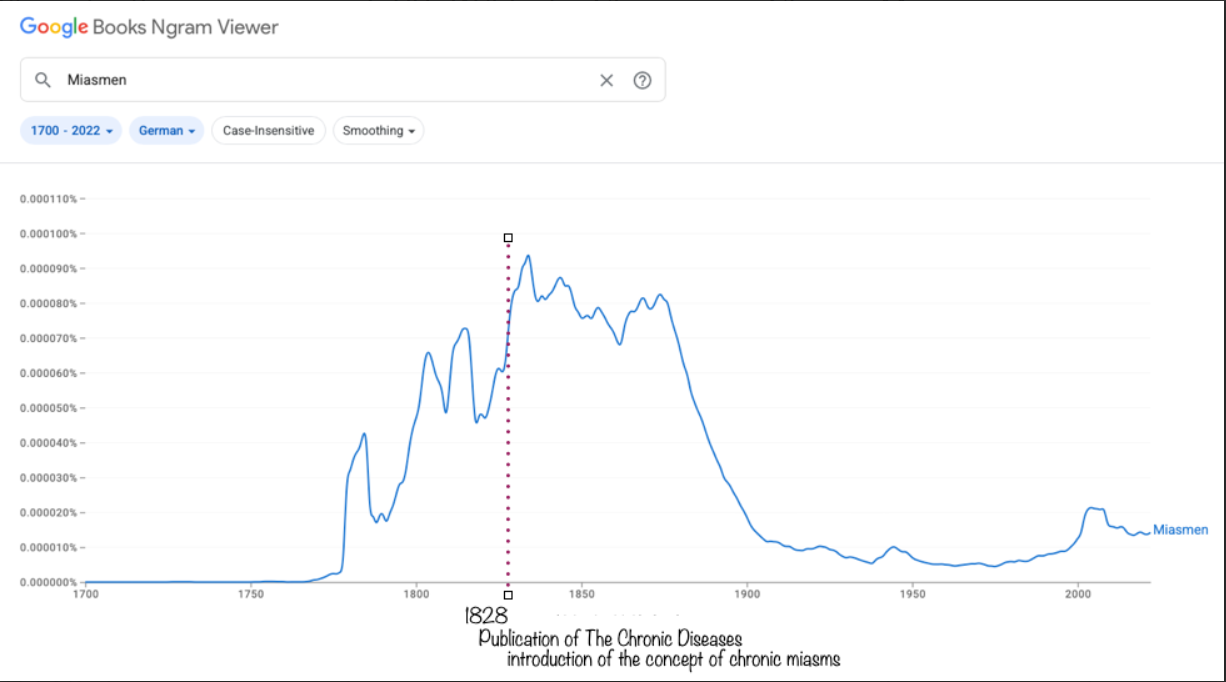

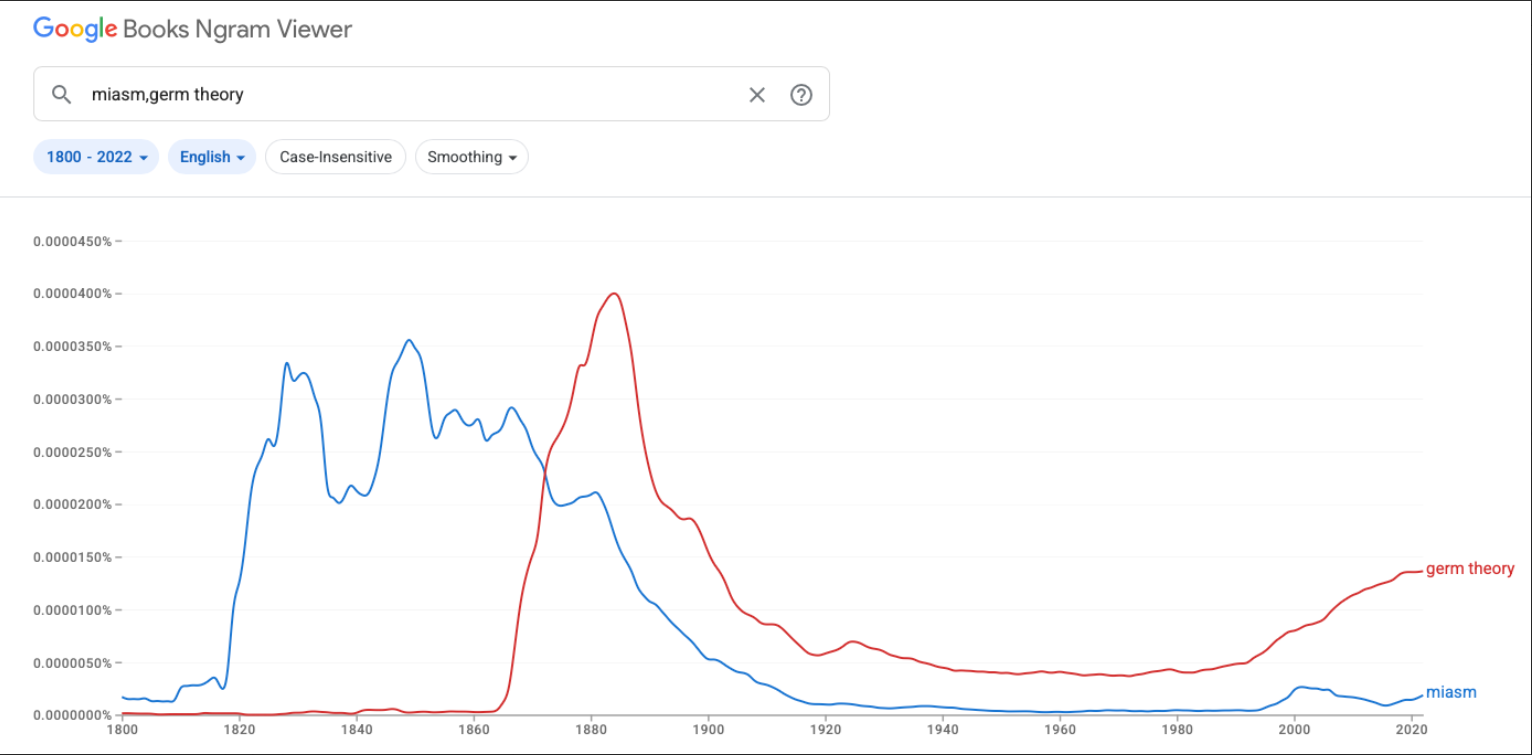

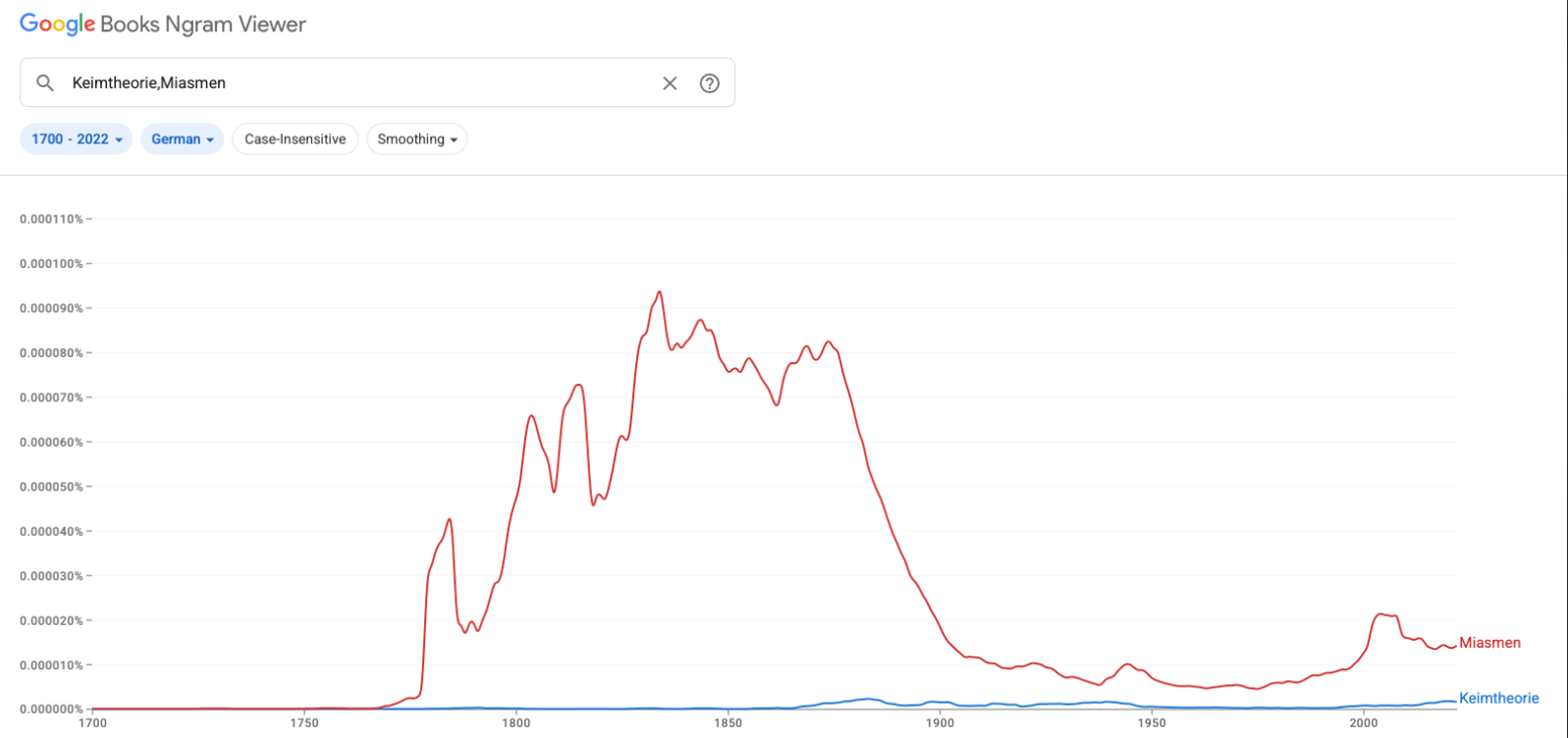

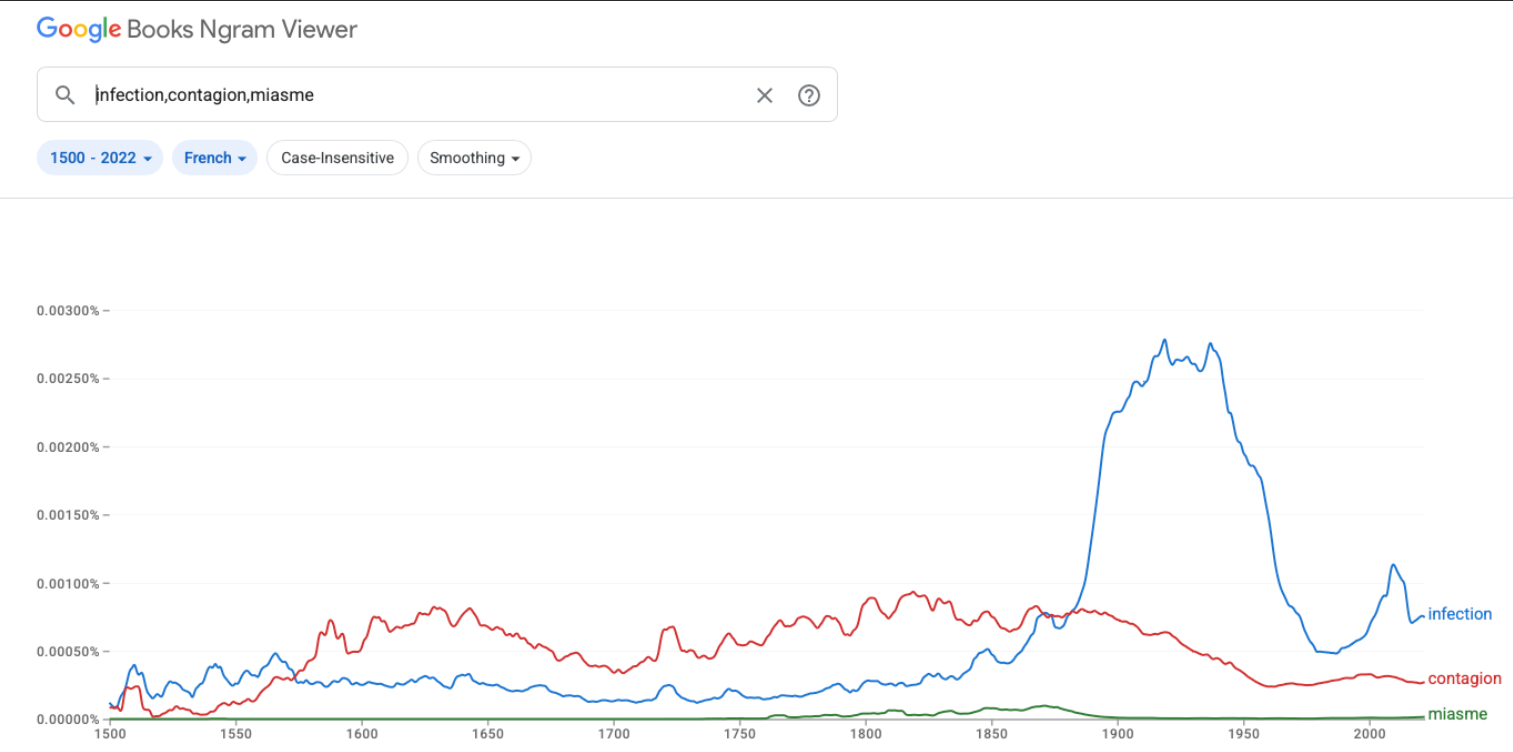

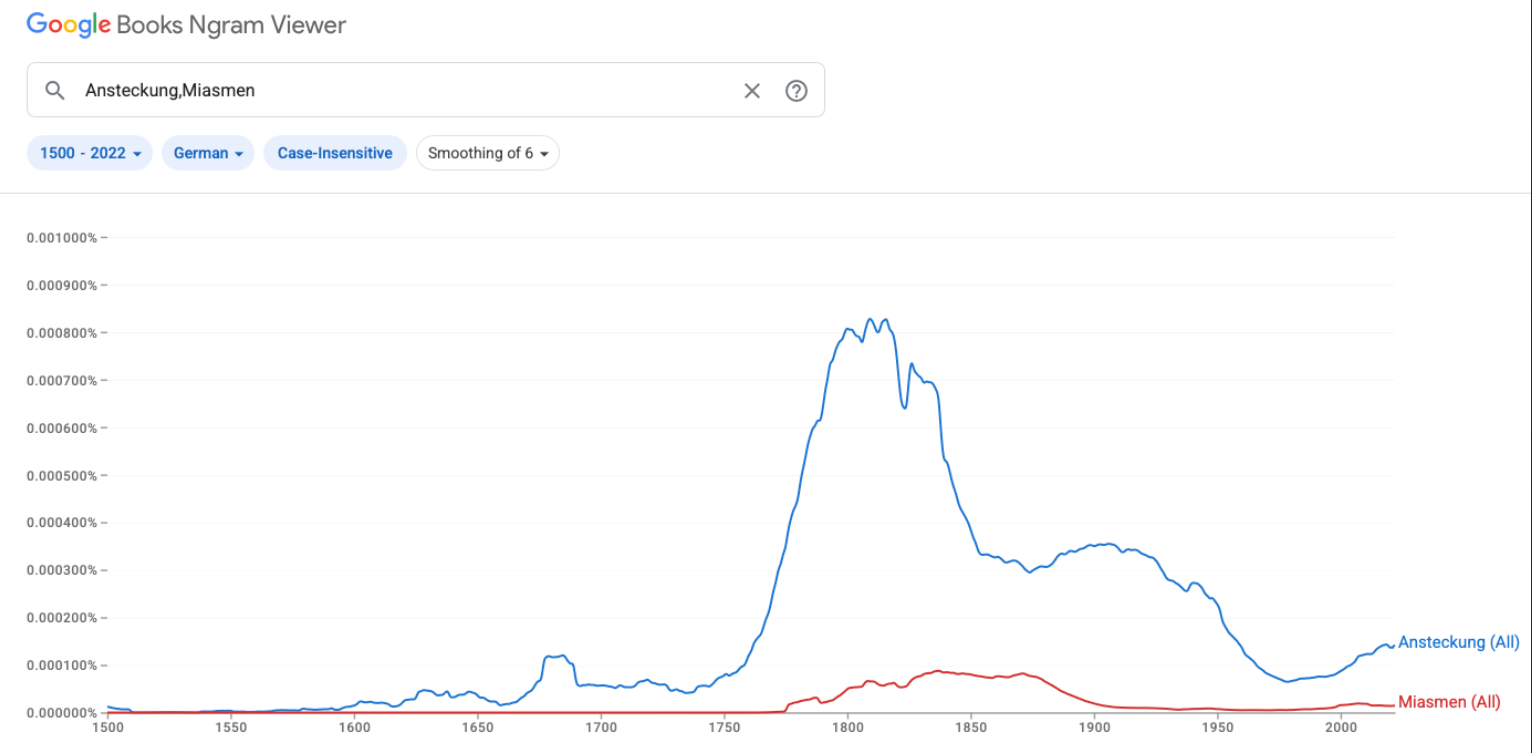

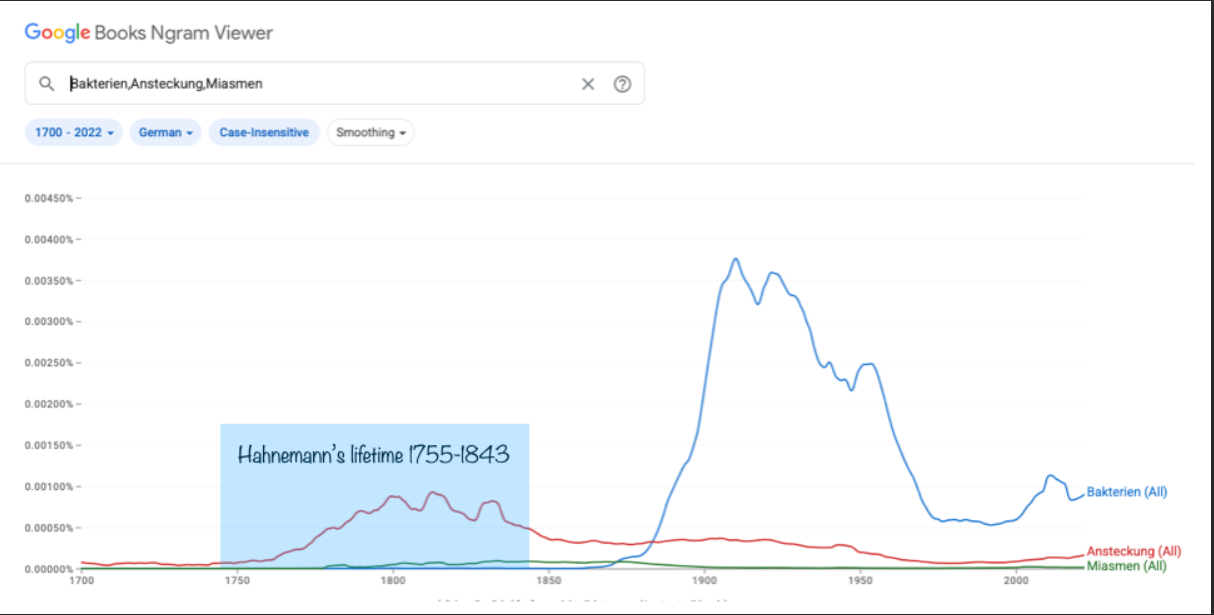

The Google Ngram viewer (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Books_Ngram_Viewer) displays the frequency of appearance of a term or phrase in the world’s literature from 1500 through the present, normed to the number of words in publication in a given year. I’ll be relying on these throughout to trace the development of concepts. Here, use of the term “miasm” (German, Miasmen) in the world’s English and German language literature:

Fig. 1 - search for "miasm" in Google's N-gram viewer, displaying the frequency of mention, normed to the number of words in publication, in the world's English language literature.

Fig. 2 - search for "Miasmen" in Google's N-gram viewer, displaying the frequency of mention, normed to the number of words in publication, in the world's German language literature.

In his search for the causes of, and the successful treatment of, chronic disease, Hahnemann discovered what he believed to be 3 chronic infectious/contagious diseases that manifested initially acutely, “of such a character that, with small, often imperceptible beginnings, dynamically derange the living organism, each in its own peculiar manner, and cause it gradually to deviate from the healthy condition, in such a way that the automatic life energy, called vital force, whose office is to preserve the health, only opposes to them at the commencement and during their progress imperfect, unsuitable, useless resistance, but is unable of itself to extinguish them, but must helplessly suffer (them to spread and) itself to be ever more and more abnormally deranged, until at length the organism is destroyed.” (Organon, §72). These were his 3 chronic miasms (chronic infectious diseases).

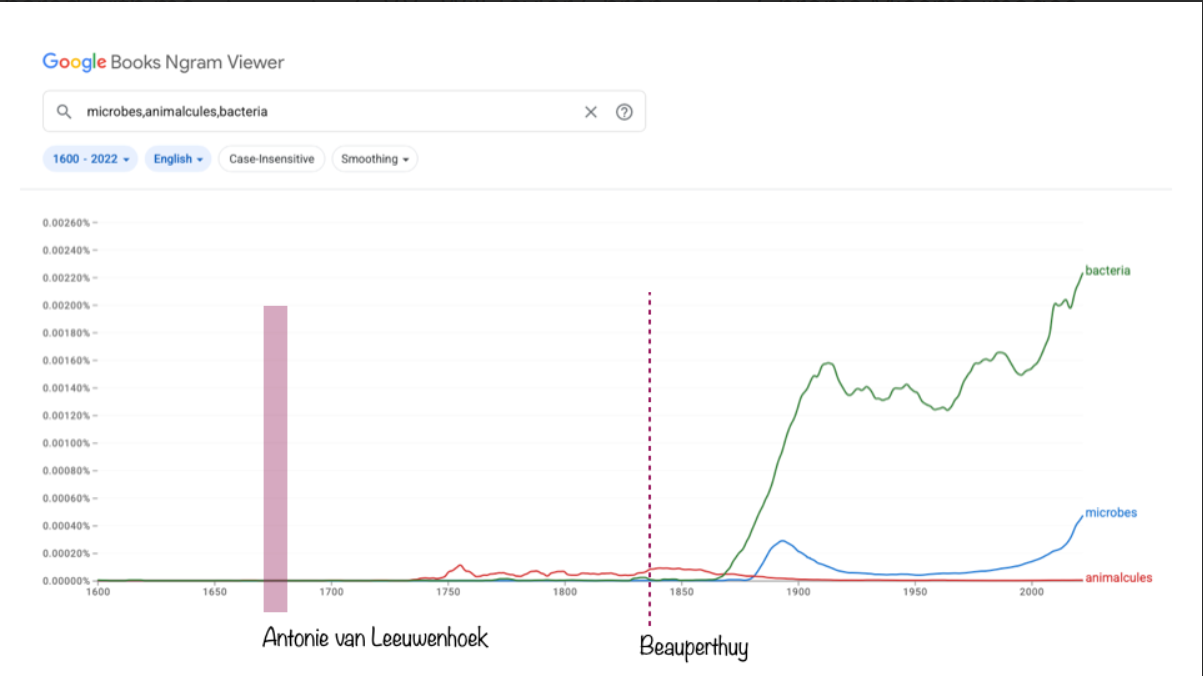

The term “Miasm” in Hahnemann’s day referred specifically to infectious disease; both to the resulting disease and its presumed causative agent. The infectious agents of disease were not understood in Hahnemann’s day, and various hypotheses were put forward. Although contemporary germ theory was not delineated until the late 1800s, well after Hahnemann’s death, microscopic living creatures as infectious agents of disease had been speculated on as early as 36 BC (the Roman statesman Marcus Terentius Varro wrote, in his Rerum rusticarum libri III (Three Books on Agriculture) “Precautions must also be taken in the neighborhood of swamps... because there are bred certain minute creatures which cannot be seen by the eyes, which float in the air and enter the body through the mouth and nose and there cause serious diseases.” Galen speculated, in On the Different Types of Fever (c. 175 AD) that plagues were spread by "certain seeds of plague", which were present in the air. In 1546, the Italian physician Girolamo Fracastoro published De Contagione et Contagiosis Morbis (On Contagion and Contagious Diseases), a set of three books covering the nature of contagious diseases, the categorization of major pathogens, and theories on preventing and treating these conditions. Fracastoro blamed "seeds of disease" that propagate through direct contact with an infected host, indirect contact with fomites on surfaces, or through particles in the air. Anton van Leeuwenhoek reported detailed observations of microorganisms in the 1670s, describing these as “diertjes” (little animals), and speculated on their potential role as agents of infectious disease. Henry Oldenburg later translated this as “animalcules.” The German Jesuit priest and scholar Athanasius Kircher had earlier described what he called “worms” observed under his microscope in the blood of victims of the 1656 bubonic plague of Rome, suggesting that these were the infectious cause of the epidemic. In 1700, the French physician Nicolas Andry argued that microorganisms he called "worms" were responsible for smallpox and other diseases. In 1838, Louis-Daniel Beauperthuy, a French tropical medicine specialist, pioneered the use of microscopy in relation to diseases and independently developed a theory that all infectious diseases were due to parasitic infection with "animalcules" (microorganisms), presenting his theory before the French Academy of Sciences.

Fig. 3

Hahnemann lived in an era when these ideas were in evolution. As a multilingual scholar, he was certainly familiar with these speculations & observations. We see him embrace the notion that malaria (“intermittent fever”) resulted from exposure to the emanations of “marsh air” (mal'aria is a contraction of mala aria, ‘bad air’), but also embrace the existence of infectious microorganisms. Describing an “acute miasm,” in The mode of propagation of the Asiatic cholera, 1831, he wrote:

“On board ships - in those confined spaces, filled with mouldy watery vapours, the cholera-miasm finds a favourable element for its multiplication, and grows into an enormously increased brood of those excessively minute, invisible, living creatures, so inimical to human life, of which the contagious matter of the cholera most probably consists … The cause of this is undoubtedly the invisible cloud that hovers closely around the sailors who have remained free from the disease, and which is composed of probably millions of those miasmatic, animated beings, which, at first developed on the broad marshy banks of the tepid Ganges, always searching out in preference the human being to his destruction and attaching themselves closely to him …”).

“Miasm,” a general term for infection without specific reference to the nature of the infectious agent, had to suffice for the lack of a vocabulary to describe the concept of infection more specifically. In retrospect, it’s often suggested that “miasm” referred specifically to the influence of imagined vapors emanating from decomposed matter as opposed to that of “germs,” but that distinction that can only be applied in retrospect, and did not exist prior to the 1880s with the advent of modern germ theory.

Hahnemann did not possess the means to directly observe these hypothetical “excessively minute, invisible, living creatures,” but speculated on their existence & mode of transmission based on the writings of those referenced above. John Snow demonstrated the propagation of cholera in public water supplies in 1854; Vibrio cholerae was first identified in patients with Asiatic cholera by the Italian physician Filippo Pacini in 1854, 24 years after Hahnemann’s speculations, and was confirmed as the infectious agent of the Asiatic cholera by Robert Koch 40 years after Hahnemann’s death, in 1883.

As early as the first edition of the Organon (1810), well before his writings on the chronic miasms, Hahnemann referred to the agents of infectious disease as “miasms:” §49 in he first edition of the Organon -

“Certain diseases are caused by a special agent of contagion (an individual miasm of a sufficiently definite kind), for instance, the plague of the Levant, small-pox, measles, true smooth scarlet fever, venereal disease … as well as rabies, whooping-cough, … etc.”

Here we see the use of the German term Miasmen (miasms) in the German literature both before and after Hahnemann’s employment of it to describe the origins of chronic disease:

Fig. 4

We’ll sometimes see it suggested that germ theory “replaced” “miasm theory” as a theory of the nature of infectious disease - it would be more accurate to suggest that germ theory emerged in the late 1800s from these earlier speculations as a clarification of the understanding of the nature of infectious (miasmatic) disease.

Fig. 5 - Google N-gram search for "miasm" and "germ theory" in the English language literature, 1800-present

Fig. 6 - Miasmen, Keimtherorie (germ theory) in the German literature, 1700-present

Fig. 7 - infection,contagion,miasme in the French literature, 1500-present

Fig. 8 - Anstekung (infection) & Miasmen in the German literature, 1500-present

Fig. 9 - Ngram serach for Bakterien (bacteria),Ansteckung (infection),Miasmen in the German literature, 1700-present

In §72 in the Organon (6th edition; first referenced in the 4th edition, in 1829, the year following publication of The Chronic Diseases) Hahnemann suggests that chronic diseases arise “von dynamischer Ansteckung durch ein chronisches Miasm” [from dynamic infection/contagion by a chronic miasm]. In The Chronic Diseases, he wrote “all [chronic diseases] have for their origin and foundation constant chronic miasms, whereby their parasitical existence in the human organism is enabled to continually rise and grow.” Note “parasitical existence in the human organism is enabled to continually rise and grow;” these are chronic infections. These are infectious diseases “of such a character that, with small, often imperceptible beginnings, dynamically derange the living organism, each in its own peculiar manner, and cause it gradually to deviate from the healthy condition, in such a way that the automatic life energy, called vital force, whose office is to preserve the health, only opposes to them at the commencement and during their progress imperfect, unsuitable, useless resistance, but is unable of itself to extinguish them, but must helplessly suffer (them to spread and) itself to be ever more and more abnormally deranged, until at length the organism is destroyed.” (Organon, §72).

It’s been erroneously suggested that Hahnemann’s “Psora theory” replaced an earlier “coffee theory” of the nature of chronic disease. In 1803, Hahnemann published his Wirkungen des Kaffees (Treatise on the effects of coffee), in which he described coffee as a common cause of medicinal disease. This was not an attempt to describe the origins of chronic disease, and was not “replaced” or supplanted by his thoughts in The Chronic Diseases. In the 5th/6th edition of the Organon, these sit side -by-side in §s74-79, with the effects of coffee (not mentioned explicitly) described as medicinal disease (§75) and “diseases inappropriately named chronic” (§77), to be treated by its discontinuation rather than by homeopathic treatment; and Hahnemann references that treatise in his discussion of Psora in The Chronic Diseases, stating (p. 109)

Coffee has in great part the injurious effects on the health of body and soul which I have described in my little book Wirkungen des Kaffees.

In The Chronic Diseases (1828), Hahnemann described his initial model of chronic disease as arising from chronic infection with Syphilis. Syphilis was recognized to be contagious by direct venereal contact, but the infectious agent - the spirochete Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum - was identified only in 1905. Based on this example, he proposed chronic diseases to result from another chronic venereal infection, which he described in detail in its acute presentation and termed Sycosis, and a proposed highly contagious non-venereal chronic infection, which he termed Psora, to which he attributed 7/8ths of all chronic disease.

Heritability?

It’s common to consider the chronic miasms to represent heritable disease or dispositions to disease. However, Charles Julius Hempel, the English translator of Hahnemann’s The Chronic Diseases, correctly observed that Hahnemann never once mentioned the possibility of heritability of the chronic miasms.

We have, in a letter to Stapf, In Bradford’s The Life and Letters of Dr Samuel Hahnemann, in Hahnemann’s own words:

” Von Gersdorff [Heinrich A. Von Gersdorff] already suspected the heredity Erblichkeit of Psora, and I think I confuted him [proved him wrong].

A footnote to aphorism §284 in the English translation of the 6th edition of Hahnemann’s Organon, written not by Hahnemann, but appended to the text by Richard Hael, reads:

most infants usually have imparted to them Psora through the milk of the nurse, if they do not already possess it through heredity [Erbshaft; legacy] from the mother ...

This is often erroneously attributed to Hahnemann, appearing in his text without explanation of its source from Hael, and the proposed heritability of the chronic miasms has become central in contemporary homeopathic canon. In The Chronic Diseases, Hahnemann suggests that Psora might be transmitted from an infected mother to the infant in the process of birth, or by a midwife or wet-nurse, but does not suggest hereditary transmission.

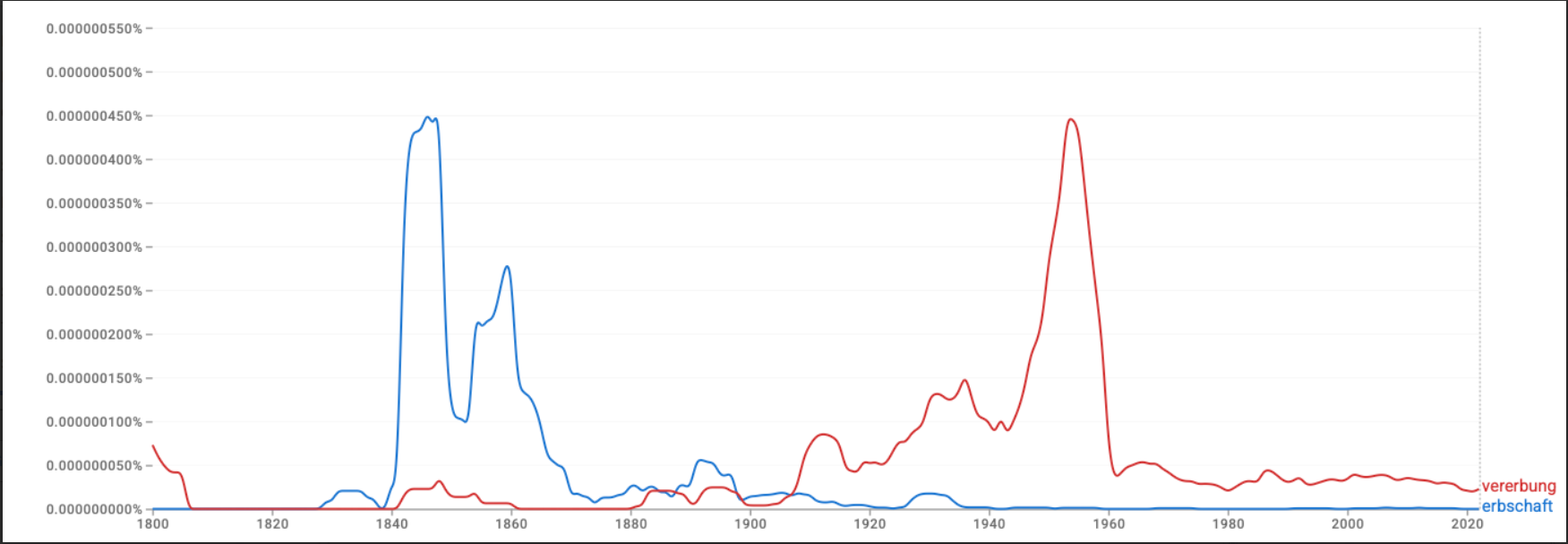

The concept of biological heredity was developed in the late 1800s, well after Hahnemann’s era, following Gregor Mendel’s observations in the 1850s-60s and the rediscovery of his work c. 1900. The German term Vererbung, in use principally after 1900, has been adopted to describe biological heredity and hereditary transmission. The term Erbschaft (legacy), which refers to inheritance in a more general sense, had earlier been used to describe the inheritance of physical appearance and general characteristics as well as the inheritance of property.

Fig. 10 - Google Ngram search for Vererbung and Erbschaft in the world's German literature

Although other authors subsequent to Hahnemann referenced purported heritability, John Henry Allen, in The Chronic Miasms (1908), was the first to explicitly assert that the chronic miasms were primarily inherited states, and that children were born sick. Recall that he ascribed to the notion that “the Creator tells us plainly that sin is behind all the ills to which man is heir;” the heritability of chronic disease essentially represented “the sins of the fathers visited on the children.” I’d suggest reading J.H. Allen's The Chronic Miasms only to appreciate how distorted Hahnemann’s teachings have become in the hands of others. Return to the opening 3 paragraphs of this essay.

Whether these individually or collectively are heritable epigenetically or acquired transplacentally, or only acquired at the time of birth or in neonatal exposure or thereafter, are interesting questions that deserve careful attention; we know that Syphilis may be acquired transplacentally as congenital Syphilis; human papillomavirus is not transmitted congenitally; Psora remains a mystery. The assumption by many of our homeopathic authors of the heritability of the chronic miasms appears to be rooted more in adoption of dogma, which is not derived from Hahnemann, but from subsequent authors largely misrepresenting his thought, than in careful observation.

Hahnemann described these as chronic infections [chronic miasms], acquired during one’s lifetime.

Margaret Tyler wrote (in her book Hahnemann's Conception of Chronic Disease as Caused by Parasitic Micro-Organisms, 1940), “True natural Chronic Diseases are those which owe their origin to a chronic parasitic miasm or germ, i.e. a parasitic micro-organism in our terms.” Stuart Close, in The Genius of Homeopathy (chapt. Chapter VIII: General Pathology of Homœopathy) also states this clearly.

This is not a “digression to allopathic concepts.” The origins of disease is a topic of interest in any system of medicine, whether “allopathic,” homeopathic, ayurvedic, or contemporary Western medicine. Kent rejected the conclusions of germ theory; Hahnemann anticipated germ theory from its early roots, and apparently embraced it. We need to recall that Hahnemann originally termed his system the “doctrine of specifics,” only adopting the term homœopathy in 1808; he continued to entertain the notion of “specifics” related to the cause of disease throughout his career, clearly evident in his writings on the chronic diseases.

Other morbific influences may result in disease, and the results of these insults may sometimes be consistent enough to define the resulting disease by its cause, as we do with acute and chronic miasms. Radiation exposure may result in radiation sickness and in somatic mutations contributing to cancer, but this is not a “radiation miasm.” Bruises do not result from a “contusion miasm.” Psychological trauma does not result from an “abuse miasm.”

The chronic miasms are chronic infectious/contagious diseases. Diseases in their own right - not merely dispositions to disease. We can legitimately consider other causes of longstanding disease (“chronic” as Hahnemann used it implies something beyond merely longstanding; see §72 in the Organon, referenced above). However, these morbific causes, when they appear to result in chronic disease, most often are merely proximate triggers, predicated on the pre-existence of a chronic disease.

See Hahnemann’s footnote to §206:

… we must not allow ourselves to be deceived by the assertions of the patients or their friends, who frequently assign as the cause of chronic, even of the severest and most inveterate diseases, either a cold caught (a thorough wetting, drinking cold water after being heated) many years ago, or a former fright, a sprain, a vexation (sometimes even a bewitchment), etc. These causes are much too insignificant to develop a chronic disease IN A HEALTHY BODY, to keep it up for years, and to aggravate it year by year, as is the case with all chronic diseases from developed Psora. Causes of a much more important character than these remembered noxious influences must lie at the root of the initiation and progress of a serious, obstinate disease of long standing; the assigned causes could only rouse into activity the latent chronic miasm.

These chronic diseases may present with unique susceptibilities to additional morbid influences, but are more than merely states of susceptibility or diatheses; they are diseases in their own right.

James Tyler Kent, and John Henry Allen (author of The Chronic Miasms) adopted a Swedenborgian concept of disease that denied the significance of infectious organisms, declaring disease to arise from distortions of the Will and Understanding, and that the chronic miasms represented predispositions to disease born from moral transgression; J.H. Allen wrote:

… lying behind Hahnemann’s theory, we see sin to be the parent of all the chronic miasms, therefore the parent of disease. It was never intended, nor can it be possible, that disease could have any other origin. Man was the disobedient one, and through his disobedience came disease. “The wages of sin is death.” Nature may, in some ways, assist in bringing about disease in man, but nature did not become his enemy until after his fall. Yea, even all nature, too, is perverted, for all has come under the curse of man’s fall. Therefore, why should we blame the climate or the elements or bacteria or micro-organisms, when the Creator tells us plainly that sin is behind all the ills to which man is heir?

Breaking from Hahnemann’s understanding, Kent and J.H. Allen viewed venereal miasms not as infectious diseases propagated by physical contact and the transmission of an infectious agent, but as the result of impure thoughts of sexual misconduct; Psora was equated with original, non-venereal sin.

Psora... is a state of susceptibility to disease from willing evils.

Kent; Lectures in Homeopathic Philosophy, p.135

Recall that Kent’s medical training consisted of one incomplete semester at John Scudder’s Eclectic Institute, while Hahnemann, Hering, and many others in our lineage had full medical training.

H.A. Roberts suggested that Hahnemann chose the name Psora to represent the Hebrew word ‘tsorat,’ which might be interpreted as a “fault” and understood as “sin” or “transgression.” Had this been the case, Hahnemann, who was fluent in Hebrew and Aramaic, as well as Greek, Latin, Arabic, and the major languages of Western Europe, would undoubtedly have used tsorat, or a term more appropriate to describe sin (e.g., chot, shaal, hitykafa, pheshoa, takala in Hebrew), rather than the Greek Psora (itch, skin disease).

Richard Hughes, who considered Hahnemann’s theories of chronic disease to have been the result of senility, suggested considering the chronic miasms to be diatheses or states of susceptibility to disease, while Hahnemann suggested these to be chronic diseases in their own right.

Only and precisely 3?

Hahnemann wrote, in The Chronic Diseases,

In Europe and also on the other continents so far as it is known, according to all investigations, only three chronic miasms are found …

When John Henry Allen wished to add a 4th, PseudoPsora, rather than break this canonical troika, he proposed this to be an awkward “hereditary marriage of Psora & Syphilis.”

In The Principles and Art of Cure by Homœopathy, H.A. Roberts proposed the classification of Hahnemann’s 3 chronic miasms according to what he considered the 3 fundamental physiologic principles of deficiency (Psora), excess (Sycosis), and destruction (Syphilis), proposing a fundamental triad based on these properties. Sánchez Ortega, in Notes On The Miasms (1977), elaborated on this, considering these to be fundamental properties defining the chronic miasms. In a very simplistic sense, the sycotic figwart might be seen as a growth of excess tissue, the syphylitic chancre as destructive; but examples of excess, deficiency, and destruction can be seen in all disease. Note the many ulcerative symptoms and warts/condylomata and tumors of Psorinum and of Sulphur. Many of the symptoms Hahnemann described in his characterization of latent Psora could be interpreted as expressions of excess or destruction. Although Hahnemann attributed the genital figwart to Sycosis, he described common somatic warts to result from Psora; and he considered tuberculosis (phthisis, consumption, and scrofula), one of the most destructive diseases known, to be an expression of Psora.

Prafull Vijayakar has suggested association with the 3 primary germ layers of the developing embryo - ectoderm (Psora), mesoderm (Sycosis), and endoderm (Syphilis), with each resulting in disease manifesting primarily in these tissues, and also with a proposed triad of cellular functions involving homeostasis (Psora), growth / repair (Sycosis), and defense / destruction (Syphilis).

Hahnemann merely described what he believed to be 3 chronic infectious diseases, two (Syphilis and Psora) of great, and one (Sycosis) of rather minor significance. He did not dogmatically assert that we might not discover other chronic infectious diseases to add to these 3, or that these were rooted in some fundamental trinity. Both Boenninghausen and Hering speculated on the possibilities of chronic miasms beyond Hahnemann’s three.

Constantine Hering wrote, in his forward to the English translation of the 3rd edition of The Chronic Diseases:

Upon the same ground that Hahnemann carefully distinguished from the disease the symptoms which owed their existence to dietetic transgressions, or to medicinal aggravations ; upon the same grounds that he acknowledged as standing and independent diseases the acute miasms, known as purpura, measles, scarlatina, small pox, whooping cough, etc., or that he distinguished the venereal miasm into Syphilis and Sycosis, we may afterwards, if experience should demand it, subdivide Psora into several species and varieties. This is no objection to Hahnemann's theory. Hahnemann has taken the first great step without denying the faculty of progressive development inherent in his system. But let improvements be made in such a way as to become useful, not prejudicial to the patients. We ought to raise our superstructure upon Hahnemann’s own ground, in the direction which he has first imparted to his doctrine.

And Boenninghausen wrote, in his Anamnesis of Sycosis,

I do not wish to deny by any means that there may be perhaps beside the three above mentioned anamnestic indications, and beside the medicinal diseases, one or another additional miasm to which may be ascribed a similar influence on health. Nevertheless such a miasm has not been so far proved by means of demonstrative documents and it must therefore be left to future investigations.

In his 1999 book The Substance of Homoeopathy, Rajan Sankaran introduced the notion that we might classify remedies, and the cases requiring them, according to properties that would associate them with 10 “miasms,” proposing 7 categories that he named the acute (distinct from “acute miasms” as used by Hahnemann), ringworm, malarial, typhoid, leprous, cancer and tubercular “miasms,” in addition to 3 categories named for the chronic miasms described by Hahnemann. These were advanced as categories encompassing broad general characteristics for use in remedy selection, without the inference that these described the etiology of disease. My concern with these is not in the expansion from 3 to 10, but in representing these categories of convenience - even those 3 named for Hahnemann’s 3 chronic miasms - as “miasms.”

Hahnemann had earlier suggested that some remedies were close to “specifics” for the chronic diseases he described; Mercury for Syphilis, Thuja and Nitric acid for Sycosis, and Sulphur, along with the 48 remedies in the provings section of The Chronic Diseases, for Psora, but did not suggest that remedies were limited in their applicability to particular miasmatic diseases. He may have considered Mercury a near-specific in the treatment of Syphilis, but found use for it in diseases other than Syphilis as well. We frequently, e.g., find use of Mercury in the treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis or acute otitis media, acute diseases, without the implication that these represent syphilitic disease. A discussion of the utility of these categories in remedy selection is beyond the scope of this writing; I’d merely like to suggest that, if these are to be adopted, they be named something other than “miasms” (= infectious diseases), which they are not intended to represent.

References:

Thomas Lindsley Bradford, The Life and Letters of Dr Samuel Hahnemann http://www.homeoint.org/books4/bradford/chapter34.htm

Samuel Hahnemann, 1831, The mode of propagation of the Asiatic cholera https://courses.homstudies.com/mod/page/view.php?id=487

Samuel Hahnemann, 1803, Treatise on the effects of coffee https://archive.org/details/9605368.nlm.nih.gov

Samuel Hahnemann, 1828, The Chronic Diseases http://www.homeoint.org/books/hahchrdi/index.htm

James Tyler Kent, Kent, 1900, Lectures in Homeopathic Philosophy http://www.homeoint.org/books3/kentlect/index.htm

John Henry Allen, 1908, The Chronic Miasms https://www.scribd.com/document/862984875/Chronic-miasm-J-H-ALLEN

Margaret Lucy Tyler, 1940, Hahnemann's Conception of Chronic Disease as Caused by Parasitic Micro-Organisms

Stuart Close, 1924, The Genius of Homeopathy

H.A. Roberts, 1936,The Principles and Art of Cure by Homœopathy

Sánchez Ortega, 1977, Notes On The Miasms

Prafull Vijayakar, 2003, Predictive Homeopathy https://www.scribd.com/document/804519621/Predictive-Homoeopathy-Verbatim-T

Rajan Sankaran, 1999 The Substance of Homoeopathy

Part Two

Chronic Miasms - Sycosis

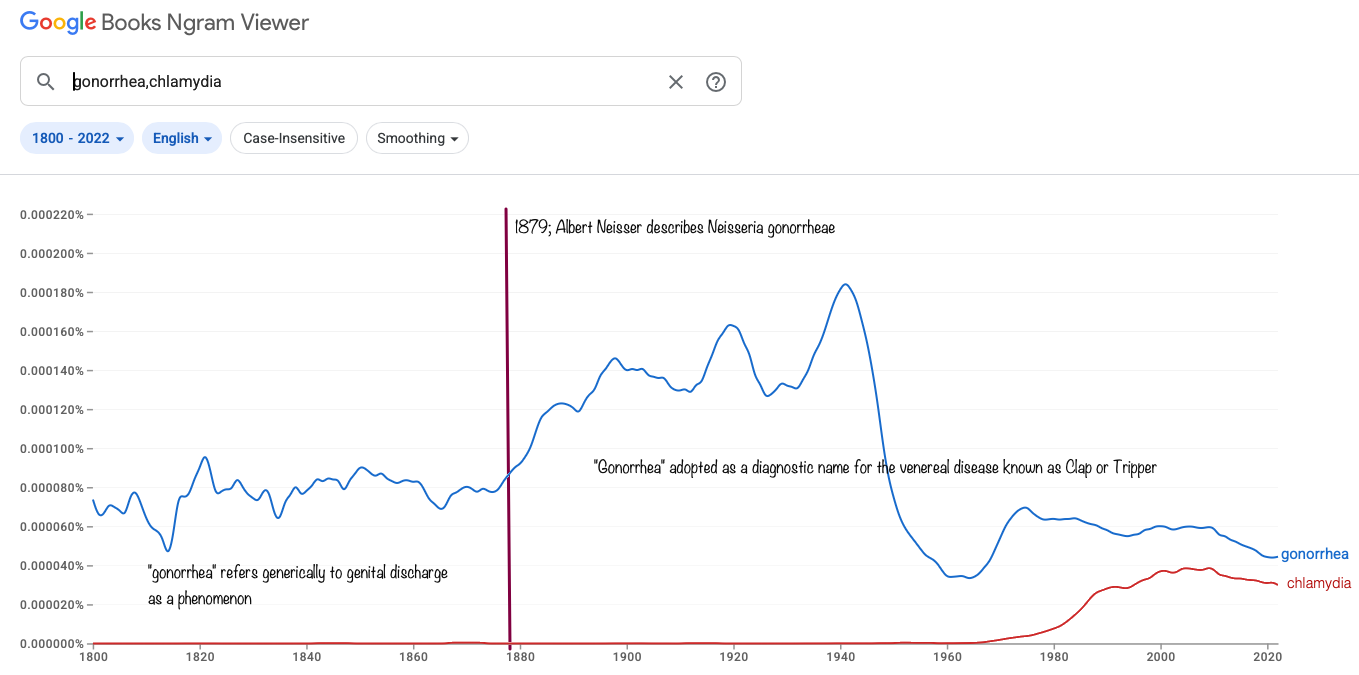

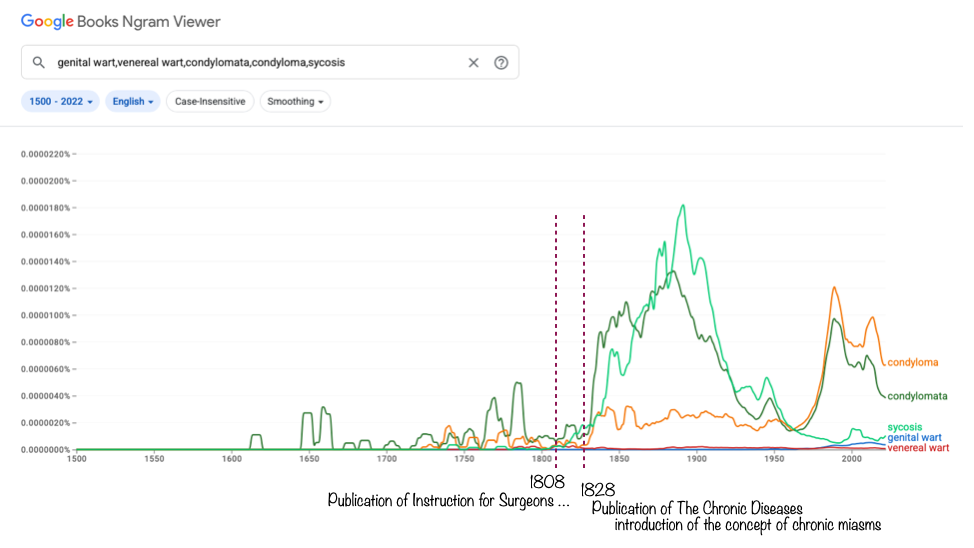

Hahnemann had previously described Sycosis in its acute venereal presentation in his 1789 essay Instruction for Surgeons Respecting Venereal Diseases. The accepted authority on venereal disease in the late 1700s through the 1800s was the Scottish surgeon John Hunter, who proposed that all venereal disease resulted from syphilis. Hahnemann broke from this dogma, and distinguished the genital figwart - condyloma accuminata

Fig. 1 - figwart, condyloma accuminata from the condyloma lata of secondary syphilis,

Fig. 2 - condyloma lata of secondary Syphilis

proposing the figwart to result from a venereal infection distinct from Syphilis. He observed that the genital figwarts that characterize Sycosis (Greek σύκο/sýko = fig) were often “attended with a sort of gonorrhœa from the urethra;” gonorrhœa in his day was a generic term for genital discharge (Greek gonorrhoia, from gonos ‘semen’ + rhoia ‘flux’). The disease we today describe as Gonorrhea was only given that name in 1879, 36 years after Hahnemann’s death, by Albert Neisser.

Fig. 3

Hahnemann described the disease we today describe as Gonorrhea (“Clap”) as Tripper (the name it still goes by in contemporary German), describing this in this essay and in The Chronic Diseases as an acute “local” malady, not implicated as a cause of chronic disease, stating “The miasm of the other common gonorrhœas [i.e., genital discharges other than that of Sycosis] seems not to penetrate the whole organism, but only to locally stimulate the urinary organs.” Reading Hahnemann’s description of Sycosis in Instruction for Surgeons Respecting Venereal Diseases and in The Chronic Diseases with our understanding today, it’s clear that Hahnemann was describing venereal wart disease, condyloma accuminata, which we can attribute not to Neisseria gonorrhea, but to condylomatous strains of human papilloma virus. Medorrhinum is not the nosode of Sycosis, but of Gonorrhea, a venereal infection that seems “not to penetrate the whole organism, but only to locally stimulate the urinary organs.” Notably, warts/condylomata/excrescences are not a symptom of Gonorrhea (I’ll capitalize this diagnostic term to distinguish it from “gonorrhœa” as a generic genital discharge). John Paterson’s unfortunately named “Sycotic co.” bowel nosode is not sycotic, but bears great resemblance to Medorrhinum and has seen success in treating Gonorrhea. The nature of venereal wart disease was poorly understood until the 1950s-70s, and persisting notions of the unitary nature of venereal disease, combined with Hahnemann’s use of the term gonorrhea generically for genital discharge, has led to confusion in attributing Sycosis to the acute venereal disease known today as Gonorrhea.

James Tyler Kent wrote, in his Lectures on Homoeopathic Philosophy (1900):

It is not generally known that there are two kinds of gonorrhoea, one that is essentially chronic, having no disposition to recovery, but continuing on indefinitely and involving the whole constitution in varying forms of symptoms, and one that is acute, having a tendency to recover after a few weeks or months. They are both contagious.

Recognizing that what was commonly referred to as “gonorrhoea” in his day (c. 1900) was actually a collection of diseases characterized by urethral/cervical discharges, that included the acute venereal disease we today refer to as Gonorrhea.

Notably, a genital discharge is not a central or consistent feature of Sycosis; Hahnemann tells us the characteristic figwarts that define Sycosis are “usually, but not always, attended with a sort of gonorrhœa [genitial discharge] from the urethra.” In §79 in the Organon he described Sycosis “the condylomatous disease,” making no mention of a discharge, emphasizing the genital wart, for which it’s named, rather than a discharge, as the defining feature of the disease.

Nearly all authors subsequent to Hahnemann in our tradition, including nearly all contemporary homeopathic authors & teachers, erroneously conflate Sycosis with Gonorrhea.

Sycosis was of little significance to Hahnemann, accounting for only a small percentage of chronic disease.

concerning Sycosis, as being that miasma which has produced by far the fewest chronic diseases, and has only been dominant from time to time. This figwart-disease, which in later times, especially during the French war, in the years 1809-1814, was so widely spread, but which has since showed itself more and more rarely.

Hahnemann, The Chronic Diseases

War, such as the Napoleonic wars of 1809-1814, is a great friend of epidemic & venereal disease.

Although the figwarts and coxcomb excrescences of venereal condyloma accuminata are characteristic of Sycosis, common warts (verruca vulgaris, verruca plana, verruca plantaris) are not of sycotic origin; Hahnemann considered these to be expressions of Psora.

Combining

Skin - Warts

Skin - Excrescences

Skin - Excrescences - Condylomata

(To account for the language used by various authors)

Gives us 192 remedies, many of these “antipsorics,” including prominently Sulphur and Psorinum.

Hahnemann provided a detailed description of the primary, acute venereal presentation of Sycosis in Instruction for Surgeons Respecting Venereal Diseases and in The Chronic Diseases, but of the chronic expressions only “there arise other ailments of the body, of which I shall only mention the contraction of the tendons of the flexor muscles, especially of the fingers.” (The Chronic Diseases) The primary significance of Sycosis, was in its potential confusion with secondary syphilis in its primary, acute presentation.

Note that

Extremities - Contraction of muscles and tendons

and

Extremities - Contraction of muscles and tendons - fingers

List a great many remedies, including many that cannot be considered “antisycotics.” Both include Merc. and Sulph., and are not exclusive expressions of Sycosis.

In his essay Anamnesis of Sycosis, Boenninghausen attempted to create a description of Sycosis by extracting the “Special Symptoms of Thuja,” which Hahnemann had described as a near-specific for Sycosis, which were not shared with Sulphur or Mercury, filtering out expressions of psora & syphilis and presumably leaving only those of Sycosis. This was clever, but the conclusion that these are expressions that characterize Sycosis is a stretch, both in inclusion and exclusion.

Other attempts to describe the chronic expressions of Sycosis have been made by James Tyler Kent in his Lectures on Homeopathic Philosophy, John Henry Allen in The Chronic Miasms, H.A. Roberts in The Principles and Practice of Homeopathy, Sánchez Ortega in Notes On The Miasms , and Harimohan Choudhury in Indications of Miasms. This last is worthy of cautious attention, tho all suffer from Kent’s preoccupation with sexual degeneracy, the notion that “sin [in this case, venereal misconduct] is behind all the ills to which man is heir,” and H.A. Roberts’ notion of “excess” as a fundamental property.

John Henry Allen, Author of The Chronic Miasms, believed that Psora had receded in importance since Hahnemann’s day, and that Sycosis was presently (c. early 1900s) the dominant cause of chronic disease, affecting ~80% of the population, attributing this in part to Gonorrhea and in part to vaccinosis, while still clinging to his belief that “sin [rather than infection] is behind all the ills to which man is heir.” He reclassified the bulk of Hahnemann’s antipsoric remedies as anti-sycotic or “polymiasmatic.”

The self-loathing that we tend to think of as "sycotic" derives from “special symptoms of Thuja” generalized to represent Sycosis:

Mind -

Contemptuous - self -of

Reproaching oneself

Delusions -

body - ugly; body looks

criminal - he is

dirty - he is

sinned - one has

worthless; he is

wrong - done wrong; he has

But this is contaminated by Kent’s story of self-reproach related to venereal “sin,” which extends to syphilis as well. And note that Merc., Sulph., Psorinum, and Syphilium all exhibit symptoms of self-reproach; this not unique to sycosis.

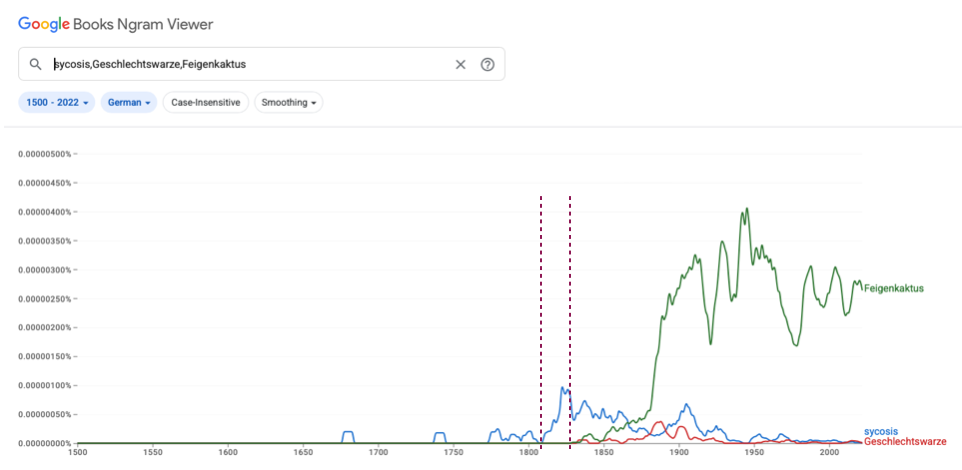

A literature search for Sycosis is complicated, as this term has been applied to other conditions, including by Galen (2nd century A.D), Archigenes (1st century A.D.), and Celsus (1st century A.D.) who defined Sycosis as exanthemata of the beard, also called mentagra (μανταγρες), or wild lichen. Contemporary medicine applies the term to inflammation of the hair follicles in the bearded part of the face, caused by bacterial infection.

Nevertheless, most references to Sycosis, in both the English and German literature, appear to parallel references to genital/venereal warts, and occur subsequent to Hahnemann’s writings on the topic.

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

We don’t have a nosode of Sycosis. Medorrhinum, introduced in 1885 by Samuel Swann, is often erroneously proposed to be, but this is prepared from the urethral discharge of someone infected with the gonococcus (Neisseria gonorrhea), not genital wart disease. John Paterson’s unfortunately named “Sycotic co.” bowel nosode is prepared from a diplococcus resembling the gonococcus found in the stools, bears close resemblance to Medorrhinum, and was found to be useful in treating Gonorrhea. Either Samuel Swann or Thomas Skinner introduced Sanguis menstrualis, menstrual blood from a woman purportedly with genital warts, with a scanty and unreliable “proving,” the closest we might come to a nosode for Sycosis. A thorough search in our literature and an internet search turns up no information on Sanguis menstrualis.

References:

Samuel Hahnemann, 1789, Instruction for Surgeons Respecting Venereal Diseases https://quod.lib.umich.edu/h/homeop/2088925.0001.001/23

Wikipedia - Genital Wart https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genital_wart

Wikipedia - Condyloma lata https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Condylomata_lata

Samuel Hahnemann, 1828, The Chronic Diseases http://www.homeoint.org/books/hahchrdi/index.htm

Samuel Hahnemann, 1789, Instruction for Surgeons Respecting Venereal Diseases

James Tyler Kent, 1900, Lectures on Homoeopathic Philosophy

Samuel Hahnemann, Organon of the Art of Healing, 6th edition

Harimohan Choudhury, 1988, Indications of Miasms

Boenninghausen, Anamnesis of Sycosis

John Henry Allen, 1908, The Chronic Miasms

H.A. Roberts, 1936, The Principles and Practice of Homeopathy

Sánchez Ortega, 1977, Notes On The Miasms

Harimohan Choudhury, 1988, Indications of Miasms

Author Bio

Will Taylor (03/22/1951- ) graduated from the University of Vermont College of Medicine in 1979 and completed a residency in Family Practice at St. Mary’s hospital in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, initially practicing conventional family medicine in Bethel, Maine. An painful episode of shingles led him to seek the care of a colleague practicing homeopathy, and a single dose of Rhus tox 1M sent him on a journey into homeopathic medicine, first in treating his 2 sons, who caught chickenpox from his shingles outbreak, then, after pursuing formal study with the The International Foundation for Homeopathy, as an option for patients in his medical practice. In 1993, Will pulled the plug on conventional practice and opened a practice devoted to homeopathy in Blue Hill, Maine, moving in 2001 to Portland, Oregon to teach full time at the National College of Natural Medicine. Will has served as faculty at The School of Homeopathy New York, the Homeopathic Academy of Southern California, and the Czech Medical Homeopathic Association, and has shared his experiences in homeopathy at National & State Societies in the U.S., & in Austria, Germany, Bulgaria and Slovakia, and online since the early days of the internet. He is currently retired after a disabling stroke in 2014, living in a cabin in the Maine Woods on Mt. Desert Island. His current projects include maintaining an archive of online video courses at https://courses.homstudies.com/, writing a growing collection of articles & essays at https://willtaylormd.substack.com, and a growing collection of eBooks at https://payhip.com/homstudiescom.