Integrating Homeopathy and Ayurveda: A Continuum of Healing Across Causal, Subtle, and Physical Domains

By Kirsten McGregor CCH, AHC

This article constitutes the first installment in a planned series examining the integrative ontology of Ayurveda and Homeopathy. Subsequent articles will further develop clinical, philosophical, and practical implications of the model introduced here.

Medical Lineage, Ontology, and the Question of Where Healing Begins

Medicine does more than respond to disease; it expresses how a culture understands life itself. Every medical system carries, implicitly or explicitly, an understanding of what a human being is, how illness arises, and where healing must begin. Modern biomedicine, for all its technical achievements, is largely grounded in a material framework. Disease is located in tissues, cells, genes, or biochemical pathways, and treatment is oriented toward modifying, suppressing, or removing these abnormalities. This approach has proven indispensable in acute care, trauma medicine, and surgery. Yet it remains limited in addressing chronic, systemic, and idiopathic illness—conditions in which no single lesion or biochemical cause adequately accounts for the patient’s lived experience of disease.

Ayurveda and homeopathy arise from a fundamentally different understanding of illness and cure. In both traditions, disease is not first a thing, but a process—not an object to be removed, but a disturbance of order within a living system. Matter is not denied, but it is understood as the most external and densified expression of deeper organizing principles. Healing, accordingly, cannot be confined to physical intervention alone. It must involve the restoration of coherence across multiple levels of being.

Ayurveda, whose classical formulations are preserved in the Caraka Saṃhitā, Suśruta Saṃhitā, and related texts, is among the oldest continuously practiced systems of medicine in the world. Emerging from the Vedic worldview, Ayurveda understands life as an expression of Ṛta—cosmic order—manifesting through nested layers of reality. Health is the harmonious expression of this order within the individual; disease is its disruption. From its earliest formulations, Ayurveda recognizes that imbalance arises first in subtler domains—discernment, perception, vitality—and only later crystallizes into gross pathology (1, 2).

Homeopathy, though historically much younger, emerges from a parallel vitalist lineage within Western medicine. Samuel Hahnemann’s dissatisfaction with the aggressive and often harmful practices of eighteenth-century medicine led him not toward speculation, but toward systematic experimentation. Through provings and decades of clinical observation, he concluded that disease is fundamentally dynamic rather than material, and that the physician’s task is to engage the organism’s inherent capacity for self-regulation rather than to override it (4). Although Ayurveda and homeopathy developed independently and within different cultural contexts, they converge upon a shared insight: life precedes matter, and healing must engage the level of organization at which disturbance first arises.

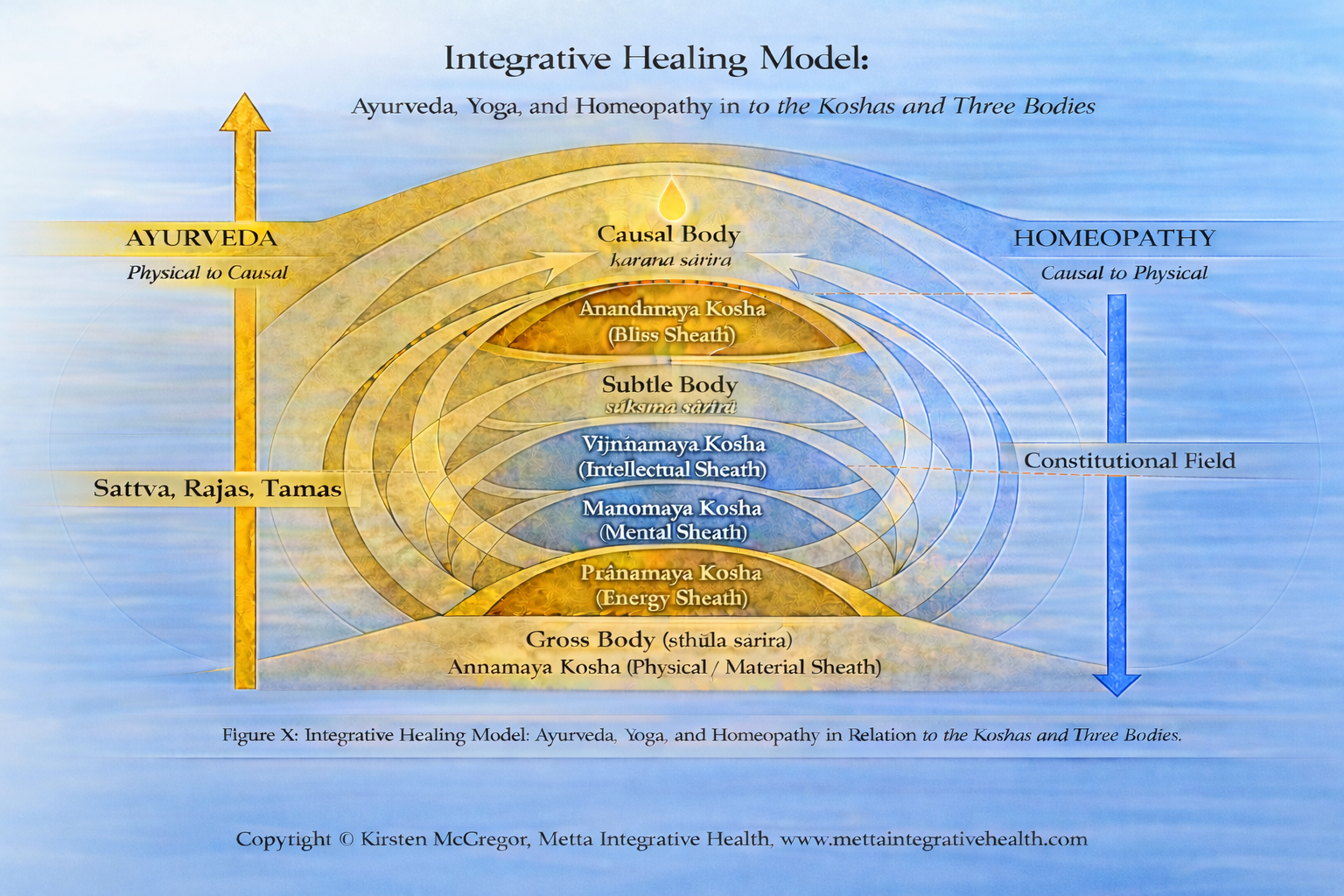

To integrate these systems coherently, a shared ontology is required—one capable of accounting for both physical manifestation and subtler forms of regulation. Ayurveda offers such a framework through its description of the human being as composed of three interpenetrating bodies (śarīras) and five nested sheaths (kośas). While these distinctions may initially appear abstract to modern readers, within their originating traditions they function as precise clinical realities rather than metaphysical abstractions.

As Dasgupta observes in his analysis of classical Indian philosophy, Indian systems do not posit mind, vitality, and matter as separate substances, but as progressively differentiated expressions of a single continuum of reality, distinguished by function rather than by kind (9). This orientation underlies Ayurveda’s insistence that disease cannot be understood—or resolved—by isolating physical processes from their subtler determinants.

The three śarīras—Kāraṇa (causal), Sūkṣma (subtle), and Sthūla (gross)—represent progressively denser domains of manifestation. The Kāraṇa Śarīra is the causal body, the domain of deep patterning and potentiality, from which orientation and individuality arises. The Sūkṣma Śarīra is the subtle body, the regulatory field in which discernment, perception, vitality, and meaning are organized prior to physical expression. The Sthūla Śarīra is the gross body, the material organism through which life becomes visible, measurable, and sustained.

Corresponding to these bodies are the five kośas as articulated in the Taittirīya Upaniṣad. These sheaths are not layers stacked atop one another, but nested fields of organization, each subtler sheath pervading and governing the denser ones. From innermost to outermost, they are the Ānandamaya Kośa (bliss sheath or causal orientation), Vijñānamaya Kośa (discernment or intellectual sheath), Manomaya Kośa (mental–perceptual sheath), Prāṇamaya Kośa (vital–energy sheath), and Annamaya Kośa (physical–material sheath) (8). Manifestation proceeds from subtle to gross; matter is the outermost expression of consciousness, not its source.

This nested understanding of embodiment carries profound implications for medicine. If disease arises first as a disturbance within the causal or subtle domains, then exclusive focus on the physical body will necessarily address effects rather than causes. At the same time, interventions that act at subtler levels must eventually express themselves physically if cure is to be complete. A coherent medical system must therefore distinguish between the point of material entry and the primary level of regulatory engagement.

Both Ayurvedic and homeopathic therapies necessarily enter the organism through the physical body. They differ, however, in the level of organization they primarily engage. Ayurveda classically begins by stabilizing the physical and vital domains—through diet (āhāra), lifestyle (vihāra), daily and seasonal rhythms (dinacaryā, ṛtucaryā), and ethical conduct (sadvṛtta)—thereby reorganizing the Annamaya and Prāṇamaya Kośas and creating conditions for deeper realignment (1,2). Ayurveda also includes refined modalities—such as prāṇāyāma, marma therapy, mantra, rasāyana, and herbo-mineral preparations (bhasmas)—that are explicitly intended to engage subtler regulatory domains (1,3).

Homeopathy, by contrast, while administered through the physical body, engages first at the level of organizing intelligence that governs perception, vitality, and form. Hahnemann’s concept of the vital force refers not to prāṇa alone, nor to nervous or metabolic activity, but to the principle that coordinates these functions into a coherent living whole. Read through the lens of the kośa model, the vital force corresponds most closely to the interface between the Ānandamaya and Vijñānamaya Kośas—the domain in which causal orientation and discernment regulate all downstream expression.

This placement is grounded in classical sources. Hahnemann defines disease as a “dynamic derangement” of the vital force rather than a material lesion, insisting that pathological changes in tissues are secondary expressions (Organon §§9–11) (4). Classical Ayurveda similarly identifies disturbances of discernment (prajñāparādha) as upstream determinants shaping disease long before physical manifestation (1). Feuerstein further clarifies that the Vijñānamaya Kośa operates as a regulatory interface through which causal orientation shapes mental, vital, and bodily expression, rather than as a locus of cognition in the modern psychological sense (3).

Taken together, these frameworks justify locating homeopathy’s primary field of engagement at the causal–discernment interface, with therapeutic effects unfolding outward into mental, vital, and physical domains. This placement also accounts for the characteristic direction of cure observed clinically in homeopathy—from shifts in perception and orientation toward functional and structural resolution—described by Hahnemann and later systematized by Kent and Vithoulkas (4,6,18).

Seen in this light, Ayurveda and homeopathy are not competing systems but complementary expressions of a single medical continuum. Ayurveda stabilizes and purifies the embodied terrain through which life expresses itself; homeopathy engages the organizing intelligence that governs that expression. Each addresses what the other leaves implicit. Together, they articulate a medicine capable of engaging the full depth and complexity of human illness.

Ayurveda, Yoga, and the Language of Manifestation: Doṣas, Guṇas, and Clinical Order

Ayurveda does not operate in isolation but emerges alongside Yoga and Sāṃkhya as part of a unified Vedic knowledge system concerned with the nature of consciousness, embodiment, and liberation from suffering. Within this broader framework, Ayurveda functions as the applied medical science, while Yoga articulates the psychology of perception and liberation, and Sāṃkhya provides the underlying ontological grammar. Together, these sister sciences describe different dimensions of a single continuum of life (1,3,8).

Central to Ayurvedic clinical reasoning are the concepts of doṣa and guṇa. The three doṣas—Vāta, Pitta, and Kapha—describe functional principles governing movement, transformation, and stability within the embodied organism. They are not substances or causes in themselves, but patterns of physiological and regulatory activity as life expresses itself through the physical and vital domains. Doṣic imbalance thus refers to dysregulation within manifestation, particularly at the levels of the Annamaya and Prāṇamaya Kośas (1,2).

The guṇas—sattva, rajas, and tamas—operate at a subtler level, describing qualitative tendencies of clarity, activity, and inertia that shape perception, cognition, and emotional response. In classical usage, guṇas do not refer to personality traits or moral categories, but to the dynamic qualities through which mind (manas) functions within embodiment. Disturbances dominated by rajas and tamas therefore describe dysregulation within manifested mental activity (1,3).

This distinction is made explicit in the Caraka Saṃhitā, which states that “the three doṣas—Vāta, Pitta, and Kapha—are the cause of all pathology in the body, while rajas and tamas are the cause of all pathology of the mind” (1). This statement does not locate the origin of disease at the psychological level, nor does it conflate mind with causal intelligence. Rather, it differentiates domains of manifestation: bodily pathology arises through doṣic dysregulation, while mental pathology arises through guṇic imbalance within functional mind. Neither category addresses the deeper regulatory strata—such as the Vijñānamaya or Ānandamaya Kośas—where orientation, meaning, and causal coherence are established prior to manifestation.

Yoga psychology further clarifies this hierarchy by locating the roots of suffering not in sensory mind or emotional reactivity alone, but in misidentification and misalignment at the level of discernment (buddhi) and causal orientation (3,8). From this perspective, disturbances observed as doṣic or guṇic imbalance represent downstream expressions of earlier disruption. This hierarchy preserves clinical precision without reducing subtle regulation to physiology or psychology.

The Subtle Body as Ontological Reality: Beyond Energy, Psychology, and Physiology

Any serious attempt to integrate Ayurveda and homeopathy must first address a persistent misunderstanding in contemporary integrative medicine: the tendency to collapse the Subtle Body (sūkṣma śarīra) into refined versions of physical or psychological processes. In modern discourse, prāṇa is frequently translated as “energy,” manas as “the mind,” and buddhi as “intellect” or cognition. While such translations may appear accessible, they fundamentally distort these concepts within their classical contexts. The Subtle Body is not an extension of the physical organism upward, nor a metaphorical overlay upon it; it is the pre-physical domain of regulation through which causal orientation becomes perception, vitality, and eventually material form.

Classical Ayurvedic and yogic texts are unambiguous on this point. The Subtle Body is not composed of measurable energy, neural activity, or biochemical signaling. Rather, it is the domain in which pattern, orientation, and relational order are established prior to physical manifestation. Feuerstein emphasizes that yogic psychology operates on a level “prior to sensory-based cognition and physiological function,” a level that cannot be adequately mapped onto modern psychological categories without distortion (3). This distinction is foundational rather than semantic, shaping how health, disease, and therapeutic action are understood.

Within this framework, the Subtle Body comprises three interrelated kośas—Vijñānamaya, Manomaya, and Prāṇamaya—each governing a distinct regulatory function. These sheaths do not correspond one-to-one with intellect, emotion, or energy as those terms are used in contemporary biomedical or psychological models. Instead, they describe successive fields of mediation between causal orientation and physical expression, articulating how life organizes itself before symptoms appear.

The Vijñānamaya Kośa, associated with buddhi, is the sheath of discernment and orientation. It governs how coherence is recognized, how meaning is integrated, and how perception is aligned with action. This is not analytical reasoning or abstract cognition, but the faculty by which the organism maintains intelligible orientation within its world. Disturbance at this level manifests clinically as chronic misjudgment, loss of direction, and repeated life patterns that undermine health despite conscious effort to change. Such disturbances often precede emotional distress and physical illness, shaping disease trajectory long before identifiable pathology emerges.

Ayurvedic texts describe prajñāparādha—the “failure of discernment” or “crime against the intellect”—as a primary cause of disease (1). This concept refers not to moral failing, but to a rupture within the Vijñānamaya Kośa: a loss of alignment between knowing and living. Clinically, this is often experienced not as illness per se, but as a persistent sense of misalignment—knowing what would support health, yet repeatedly acting otherwise.

The Manomaya Kośa governs perception, affect, and interpretive filtering. It is the domain in which experience acquires personal meaning and emotional tone. Disturbance here manifests as persistent emotional patterns, perceptual distortions, and habitual reactivity. Classical Ayurveda recognizes disturbances of manas as significant contributors to chronic disease, particularly when emotional states such as fear, grief, anger, or attachment become fixed patterns rather than transient responses (1). Emotional suffering is neither minimized nor psychologized away; it is understood as meaningful information about deeper regulatory imbalance.

The Prāṇamaya Kośa governs vitality, rhythm, and integration. Prāṇa is often defined as “energy,” but this translation obscures its function. Prāṇa is not force or power; it is the coordinating principle of animation, governing respiration, circulation, movement, sensory engagement, and metabolic transformation. Disturbance at this level manifests as dysregulation—fatigue, agitation, congestion, depletion—reflecting loss of coordination between subtler regulatory domains and physical expression. Ayurvedic practices such as prāṇāyāma, marma therapy, and regulated daily routines are designed to restore order at this level by re-establishing rhythm rather than imposing force (1,3).

Homeopathy and the Vital Force: Dynamic Disease, Constitution, and the Inner Direction of Cure

Samuel Hahnemann’s contribution to medicine cannot be reduced to a set of therapeutic techniques or a doctrine of infinitesimal doses. At its heart, homeopathy represents a profound reorientation of how disease and healing are understood. Rather than locating illness solely in material structures or biochemical processes, Hahnemann recognized disease as a dynamic disturbance within the living organism itself—a disturbance that precedes and governs physical expression. This insight situates homeopathy firmly within the vitalist lineage, while distinguishing it from earlier speculative vitalisms through its grounding in systematic experimentation and sustained clinical observation.

Hahnemann’s rejection of material causation is explicit. In Aphorism 12, he states that disease is not a material thing, but a “morbid mistunement” of the vital force (4). Structural lesions, pathological findings, and biochemical abnormalities are therefore understood as secondary expressions rather than primary causes. This perspective places homeopathy in direct alignment with the Ayurvedic understanding that disease unfolds from subtle imbalance toward gross manifestation, rather than originating spontaneously within the physical body.

Read through the kośa framework, the vital force does not correspond to prāṇa alone, nor to nervous or metabolic activity. Rather, it aligns most closely with the interface between the Ānandamaya Kośa and the Vijñānamaya Kośa—the domain in which causal orientation and discernment regulate downstream expression. At this level, coherence is established before it manifests as perception, vitality, or structure. This placement explains several consistent features of homeopathic practice: the prominence of mental and emotional symptoms in remedy selection, the depth and durability of action of highly diluted remedies, and the characteristic observation that cure proceeds from within outward.

Hahnemann underscores this orientation in Aphorism 210, where he states that the mental condition of the patient is “one of the most preeminent symptoms” guiding remedy selection (4). This emphasis is not psychological reductionism, but recognition that disturbances of regulation become most visible where organization is most subtle. Alterations in mood, perception, fears, delusions, desires and self-experience signal shifts within the organism’s governing intelligence rather than mere reactions to physical distress.

From an Ayurvedic perspective, such disturbances correspond to misalignment within the Vijñānamaya and Manomaya Kośas. When discernment and perception lose coherence, adaptive regulation falters, and the physical body becomes the eventual site of expression. Homeopathy’s clinical focus on subjective experience thus reflects a shared insight across both traditions: chronic disease originates upstream of physiology.

The concept of constitution further clarifies this orientation. In homeopathy, constitution refers not to static traits or inherited weaknesses, but to the characteristic way in which the vital force organizes perception, adaptation, and response. Constitution describes the individual’s habitual pattern of regulation—how stress is processed, how imbalance manifests, and how recovery unfolds. This understanding closely parallels the Ayurvedic concept of prakṛti, which describes the inherent pattern of physiological and regulatory tendencies present from birth, shaping susceptibility without determining destiny.

Vithoulkas expands this view by describing levels of health and susceptibility, emphasizing that constitution reflects the resilience or fragility of the organism’s regulatory systems rather than the condition of any single organ or tissue (6). This perspective reinforces a central homeopathic principle: genuine cure must address the organizing intelligence of the organism itself, not merely its outward manifestations.

While the concept of constitution clarifies how disease is patterned within the vital force, it does not yet explain why illness so often persists, deepens, or reasserts itself across time—even in the presence of appropriate treatment. It was this unresolved clinical question that led Hahnemann to extend the principles of the Organon into a deeper investigation of chronic disease. Through sustained observation, he came to recognize that long-standing illness reflects not only constitutional tendency, but the fixation of disturbance within the organism’s regulatory intelligence itself—a realization that would culminate in his articulation of the chronic miasms (5).

Chronic Miasms and the Persistence of Disease Patterns

Hahnemann’s introduction of the chronic miasms in The Chronic Diseases marks a decisive evolution in his understanding of illness. Through decades of clinical observation, he recognized that even well-selected remedies could yield only partial or temporary improvement in patients suffering from long-standing disease. This led him to conclude that chronic illness is not sustained by isolated symptoms or discrete pathological events, but by deeper, enduring disturbances in the organism’s regulatory intelligence—disturbances that shape susceptibility, recurrence, and the evolution of pathology over time (5).

In articulating the miasms—psora, sycosis, and syphilis—Hahnemann did not propose new disease entities or hidden pathogens. Rather, he identified persistent constitutional patterns: characteristic modes of response, adaptation, and compensation within the vital force itself. These miasms describe how disease reorganizes and perpetuates itself across time, even when surface manifestations are intermittently relieved. Chronic illness, in this view, reflects not ongoing external insult, but the stabilization of maladaptive regulatory patterns within the organism.

When read alongside Ayurvedic physiology, Hahnemann’s theory of miasms finds a close functional parallel in the interrelated concepts of prakṛti and saṃskāra. While prakṛti describes the individual’s innate constitutional organization, saṃskāras, by contrast, refer to the cumulative impressions formed through lived experience, adaptation, and repeated response. Over time, these impressions condition how the organism meets stress, recovers from imbalance, and reasserts equilibrium. In this sense, miasms and saṃskāras describe the same phenomenon through different philosophical languages: the progressive stabilization of maladaptive regulatory patterns within the subtle and causal domains of the organism. Disease persists not because the body fails, but because the organism has learned—at a deep level—to organize itself around imbalance.

This perspective reframes chronic disease as a problem of continuity and pattern rather than localization. Miasmatic disturbance unfolds over time, often across generations, embedding itself within the constitutional fabric of the individual. Hahnemann’s attention to inheritance, recurrence, and relapse reflects an early recognition that health and disease cannot be fully explained by immediate causes alone, but must be understood in relation to the organism’s developmental history and long-term adaptive strategies (5).

Read in this light, The Chronic Diseases does not contradict the dynamic disease model articulated in the Organon, but deepens it by introducing duration as a central dimension of pathology. While the Organon establishes disease as a dynamic mistunement of the vital force, the later work clarifies why such mistunement may persist, reorganize, and deepen over time if the underlying regulatory pattern remains unaddressed. Healing, therefore, is not a single corrective act but a gradual reorganization of the organism’s deepest regulatory tendencies—a process that unfolds along a continuum rather than through episodic intervention alone (4, 5).

Suppression, Chronic Miasms, and the Persistence of Pattern

While modern biomedicine often employs symptom suppression as a primary therapeutic goal, both classical Ayurveda and homeopathy reject the notion that symptoms are autonomous entities to be eradicated independently of the processes that give rise to them. In these traditions, symptoms are understood as meaningful expressions of adaptive effort—signals through which the organism attempts to restore balance. This shared premise explains why interventions that forcibly suppress symptoms at the physical level, without engaging the underlying disturbance of regulation, are understood to drive disease inward rather than resolve it (1, 2, 4).

Hahnemann addresses this danger explicitly in the Organon, warning that antipathic and purely palliative treatments may remove symptoms while simultaneously undermining the organism’s capacity for genuine healing (Organon §§59–63, 260–261) (4). When symptoms are silenced without engaging the disturbed vital force, the imbalance does not disappear; it is displaced. Over time, this displacement compels the organism to express disease at deeper and more consequential levels of organization.

Within the framework of The Chronic Diseases, this insight takes on even greater significance. Hahnemann recognized that repeated suppression plays a critical role in fixating disease within the organism. Acute expressions may resolve, yet the underlying regulatory disturbance remains intact, predisposing the individual to recurring or progressively entrenched patterns of illness. Chronic miasms, in this sense, are not produced by suppression alone, but suppression contributes powerfully to their consolidation by preventing resolution at the level where disturbance originates (5).

This model distinguishes between transient dysregulation and conditioned pathology. Acute illness reflects a temporary mistunement of regulatory intelligence; chronic illness reflects a learned and stabilized pattern of imbalance. Over time, the organism becomes conditioned toward particular modes of suffering, generating characteristic expressions of disease even in the absence of obvious external provocation. Disease, from this perspective, is not merely something that happens to the organism—it is something the organism has learned to do (4, 5).

A closely resonant understanding appears within Ayurveda through the concepts of saṃskāra and karma, understood here in their clinical rather than metaphysical sense. Saṃskāras are the subtle impressions left by past actions, experiences, and adaptive responses, shaping perception, behavior, and physiological regulation over time. When repeatedly reinforced, these impressions condition the organism toward particular patterns of reactivity, resilience, and vulnerability (3, 8). Karma, in this medical context, refers not to moral judgment, but to the continuity of causation—the manner in which past regulatory patterns shape present experience and future possibility (8).

From this vantage point, chronic disease reflects not merely the persistence of imbalance, but the persistence of conditioned modes of adaptation and regulation held within the subtle and causal dimensions of the organism. Just as Hahnemann’s miasms describe enduring distortions in the vital force’s organizing intelligence, saṃskāras describe patterned tendencies within the Subtle Body that predispose the organism toward particular trajectories of suffering. Neither concept implies fatalism. Both emphasize that healing must engage the level at which these patterns are held if genuine and lasting change is to occur (3, 5, 8).

Importantly, Ayurveda does not reject palliation outright. Śamana—measures that temporarily relieve symptoms—has a legitimate place within treatment when applied judiciously. Classical texts, however, consistently caution that śamana used without nidāna parivarjana, the identification and removal of causative factors, leads to chronicity and deeper pathology (1, 2). Symptoms may quiet, but the underlying imbalance remains active, seeking expression through alternative channels.

This convergence between Ayurveda and homeopathy reveals a shared clinical ethic: symptoms are not enemies to be eradicated, but meaningful expressions of the organism’s attempt to restore balance. Seen in this light, suppression is not merely a technical error, but a misunderstanding of what symptoms signify. Recognizing this prepares the ground for a more nuanced understanding of cure—one that acknowledges the necessity of supporting the organism across all levels of embodiment.

Resonance Rather Than Suppression: The Direction of Therapeutic Action

Having established why suppression deepens rather than resolves chronic disease, both Ayurveda and homeopathy articulate a shared alternative: healing through resonance rather than force. Where suppressive medicine seeks to override symptoms, these traditions aim to engage the organism’s own regulatory intelligence, allowing imbalance to reorganize from within rather than being forcibly silenced.

In homeopathy, this principle is expressed through the law of similars. Remedies are selected not to counteract symptoms, but to mirror the qualitative pattern of disturbance present within the vital force. By resonating with the existing state of imbalance, the remedy acts as a specific informational stimulus—one that the organism can recognize and respond to. Cure, in this context, is not imposed from outside; it is elicited from within, as the vital force reasserts order through its own regulatory capacity (4, 6).

Ayurveda arrives at a closely related understanding through a different therapeutic grammar. Medicines and interventions are chosen according to their qualitative relationship to the patient’s condition—through rasa (taste), guṇa (qualities), vīrya (potency), and vipāka (post-digestive effect). Whether acting through similarity, opposition, or modulation, the goal is not suppression, but alignment: restoring rhythmic coherence between the organism and its internal and external environments (1, 2).

Despite their methodological differences, both systems rely on the same underlying logic. Healing occurs when the intervention speaks the same language as the disturbance—when it meets the organism at the level where imbalance is organized, rather than attempting to correct its outermost expressions. This is why neither tradition views symptoms as targets, but as communicative events: meaningful signals through which the organism reveals how and where regulation has been disrupted.

Seen in this light, resonance is not a metaphor but a clinical principle. It explains why interventions that are subtle, individualized, and qualitatively precise can produce changes that are disproportionate to their material dose. It also clarifies why forceful or generalized interventions, even when temporarily effective, often fail to produce lasting change in chronic illness. The decisive factor is not the magnitude of intervention, but whether it engages the organism’s regulatory intelligence.

In moving beyond suppression toward resonance, Ayurveda and homeopathy articulate a medicine grounded not in control, but in cooperation with living order. What follows is not a rejection of the physical body, but a disciplined recognition of where healing must begin if it is to endure.

Obstacles to Cure: Ethical Medicine, Living Order, and the Ayurvedic Fulfillment of Hahnemann’s Mandate

One of Samuel Hahnemann’s most enduring—and often underappreciated—insights is that cure cannot be achieved through medicinal intervention alone. Throughout the later aphorisms of the Organon of the Medical Art, Hahnemann makes clear that the physician’s responsibility extends beyond the selection of a remedy to include the careful cultivation of conditions in which healing can actually occur. Disease, in his view, is sustained not only by internal disturbance, but by the ongoing influences that continually act upon the vital force.

This recognition culminates in Hahnemann’s doctrine of Obstacles to Cure. Far from being ancillary advice, this doctrine situates homeopathy within an explicitly ethical and ecological understanding of medicine. The vital force does not operate in isolation; it is continuously shaped by the individual’s diet, habits, sensory inputs, emotional life, social relationships, and environmental conditions. When these influences remain unexamined or uncorrected, even the most precisely selected remedy may act only partially or transiently, not because the remedy is incorrect, but because the terrain continually re-imposes disorder (4).

Hahnemann states this obligation with particular force in Aphorisms 260–261, where he insists that the physician must identify and remove obstacles arising from improper diet, excesses, lack of fresh air, disturbed sleep, emotional strain, and other factors that obstruct cure (4). These factors are not peripheral to pathology; they actively shape the vital force’s capacity for self-regulation. To ignore them is to undermine cure at its source.

What is striking, from a contemporary perspective, is that Hahnemann recognized the necessity of addressing these influences without possessing a fully articulated system for doing so. He repeatedly emphasizes moderation, rational hygiene, and ethical conduct, yet the medical culture of his time offered no comprehensive framework for aligning daily life, environment, and physiology in a systematic, individualized manner. This absence has sometimes been interpreted as a limitation of homeopathy. More accurately, this absence reflects historical limitation rather than conceptual deficiency.

It is precisely at this juncture that Ayurveda offers a mature and clinically elaborated fulfillment of Hahnemann’s mandate. Where Hahnemann identifies obstacles to cure in principle, Ayurveda provides detailed methods for their identification and removal. Central to Ayurvedic pathology is the doctrine of nidāna parivarjana—the removal of causative factors. Classical texts state unequivocally that no therapy can succeed if the causes of disease remain operative (1, 2).

From an Ayurvedic perspective, obstacles to cure are best understood as persistent disturbances across multiple kośas. At the level of the Annamaya Kośa, improper diet and impaired digestion compromise tissue integrity. At the level of the Prāṇamaya Kośa, irregular routines and chronic stress disrupt rhythm and vitality. At the level of the Manomaya Kośa, unresolved emotional patterns distort perception and behavior. At the level of the Vijñānamaya Kośa, faulty discernment perpetuates choices that undermine health despite conscious intention. These disturbances do not operate independently; they mutually reinforcing, continually re-impressing imbalance upon across levels of embodiment.

Seen in this light, Hahnemann’s doctrine of Obstacles to Cure reflects a profound intuitive grasp of the nested nature of regulation, even if he did not articulate it in the language of kośas and śarīras. A homeopathic remedy may initiate reorganization at the causal–subtle interface, but without correction of the ongoing influences that perpetuate dysregulation, its action may be blunted, distorted, or short-lived.

Ayurveda operationalizes this insight through concrete clinical practices. Dietary guidance (āhāra) is individualized according to constitution (prakṛti), digestive capacity (agni), disease state (vikṛti), season, and age. Lifestyle guidance (vihāra) addresses sleep, activity, sensory engagement, and relational conduct in ways that stabilize the Prāṇamaya Kośa and support rhythmic regulation. Daily and seasonal routines (dinācaryā and ṛtucaryā) are prescribed not as moral imperatives, but as therapeutic measures designed to reduce regulatory strain and prevent the continual re-imprinting of imbalance (1,2).

Among Ayurveda’s most comprehensive responses to entrenched disease is pañcakarma, a classical purification and realignment therapy developed specifically for chronic illness. Far from functioning as a purely physical detoxification, pañcakarma is understood to restore coherence across the Annamaya, Prāṇamaya, and Manomaya Kośas through staged preparation, elimination, and reintegration. In extended therapeutic courses, it operates as a systemic re-patterning intervention, removing obstacles to cure while creating the physiological, vital, and perceptual conditions necessary for deeper regulatory reorganization to occur (1,2).

Ethical conduct (sadvṛtta) occupies a central place in this framework. This is not moralism, but clinical realism: persistent relational conflict, chronic resentment, and misaligned priorities exert measurable effects on perception, vitality, and physiological regulation. Ayurveda’s ethical dimension can thus functions as preventive and corrective medicine operating at the causal and subtle levels.

Within an integrative framework, the relationship between homeopathy and Ayurveda becomes clear. Homeopathy initiates reorganization by addressing the deepest disturbance of the vital force. Ayurveda supports and stabilizes this process by removing ongoing disturbances at the physical, vital and perceptual levels. Neither system is sufficient alone in chronic illness; together, they fulfill the ethical vision implicit in Hahnemann’s work and explicit in the Ayurvedic tradition.

Subtle Pharmacology and the Refinement of Therapeutic Action: Potentization, Saṃskāra, and the Continuum of Engagement

Once disease is understood as arising within nested domains of causal, subtle, and physical embodiment, the question of how medicines are prepared assumes central importance. In both homeopathy and Ayurveda, medicinal preparation is not a technical afterthought, nor merely a means of enhancing safety or palatability. It is an extension of ontology itself. How a substance is processed determines not only its safety and efficacy, but the level of regulation with which it can meaningfully interact.

Modern pharmacology generally equates potency with concentration and therapeutic action with biochemical interaction. Within this framework, dilution implies loss, and refinement is understood primarily as extraction or isolation of active constituents. Vitalist medical systems invert this logic. Both homeopathy and Ayurveda assert—on the basis of sustained clinical observation—that therapeutic efficacy depends not solely on material quantity, but on the refinement of a substance’s mode of interaction with living regulation (4, 5).

Homeopathic Potentization: Refinement of Dynamic Action

Samuel Hahnemann’s method of potentization arose not from speculative metaphysics, but from repeated clinical observation. He found that crude doses of medicinal substances frequently aggravated symptoms, produced toxic effects, or acted only superficially, while remedies prepared through serial dilution and succussion acted more gently, deeply, and durably—particularly in chronic disease (4).

In Aphorism 269 of the Organon of the Medical Art, Hahnemann describes potentization as the process by which the latent medicinal powers of substances are liberated, rendering them capable of acting dynamically upon the organism rather than mechanically upon tissues (4). Read carefully, Hahnemann is not claiming that dilution creates new matter or that remedies act through material presence alone. Rather, he is describing a shift in the level of engagement—from material interaction toward regulatory resonance.

Homeopathic practice recognizes multiple potency scales—most commonly decimal (X), centesimal (C), and quinquaginta-millesimal/fifty millesimal (LM or Q)—each associated with distinct preparation methods and clinical applications. Lower potencies, particularly those below or near Avogadro’s limit (e.g., 6X–12C), may retain source-derived material or nanoparticulate traces and are often observed clinically to act more prominently at the level of organs and physiological function (10,11). Higher centesimal potencies (e.g., 200C, 1M and above) are traditionally associated with action at the mental–emotional and constitutional level, while LM/Q potencies—developed by Hahnemann in his later years—were specifically intended for chronic disease, allowing for gentle yet sustained action without overwhelming the organism (4).

Kent elaborates this clinical distinction through decades of bedside observation, noting that lower potencies tend to influence functional and structural pathology, while higher potencies more consistently engage the mental–emotional state and constitutional pattern of the patient. Importantly, Kent does not present this as a rigid hierarchy, but as a practical guide grounded in responsiveness rather than theory. The appropriate potency, he emphasizes, is determined not by philosophical preference but by the depth and chronicity of the disturbance, the patient’s sensitivity, and the clarity of the constitutional picture (18). Read in this way, Kent’s contribution refines Hahnemann’s principles without extending them metaphysically, offering clinicians a nuanced framework for matching the level of intervention to the level of disorder.

Burnett’s clinical work extends this potency logic further by demonstrating that constitutional action and organ affinity are not mutually exclusive. Through extensive use of organotherapy, Burnett showed that potentized remedies could exert specific, regulatory influence upon weakened organs and functional systems without acting through material replacement. Remedies such as Thyroidinum, Carduus marianus, or Reninum were employed not to substitute deficient tissue function, but to stimulate recovery through resonance with the disturbed organ field itself (19).

Importantly, Burnett did not restrict organ remedies to low potencies alone. While he often employed lower or moderate potencies (e.g., mother tinctures, 3X–30C) when targeting organ pathology, he emphasized that potency selection must follow the vitality, sensitivity, and responsiveness of the organism rather than anatomical location per se. Read in this way, organotherapy represents not a departure from homeopathic principles, but a precise application of them—operating at the interface between the Annamaya and Prāṇamaya Kośas while remaining oriented toward dynamic regulation rather than material force (19).

Importantly, this does not imply that all homeopathic remedies act beyond matter. Contemporary experimental studies have suggested that nanoparticles or nanostructures may persist in lower potencies, and that solvent systems may retain patterned organization through clustering and hydrogen-bond networks even in higher dilutions (12,13). These findings do not “explain” homeopathy, nor do they collapse it into nanomedicine. They do, however, challenge the assumption that absence of bulk matter equates to absence of informational or interactive capacity, supporting Hahnemann’s original claim that medicinal power is not reducible to material quantity alone.

From the perspective of the kośa model, potentization progressively refines a remedy’s capacity to act at subtler levels of organization. Rather than overwhelming the Annamaya Kośa through material force, the potentized remedy engages the regulatory intelligence of the organism, initiating reorganization that may first manifest as shifts in clarity, emotional tone, or vitality before expressing itself physically. This pattern of action—inner to outer, subtle to gross—is not imposed by doctrine but repeatedly observed in clinical practice.

Ayurvedic Saṃskāra: Refinement Through Transformation

Ayurvedic pharmacology arrives at a parallel conclusion through an entirely different historical and methodological pathway. Classical texts consistently insist that medicinal substances must undergo purification (śodhana) and intentional transformation (saṃskāra) before they can act safely and effectively within the human organism (1, 2). Raw substances—particularly minerals and metals—are rarely administered without extensive preparation, sometimes spanning months, years, or even generations.

It is important to clarify that the term saṃskāra is used in multiple technical senses within Ayurveda. In pathogenesis and psychology, saṃskāras refer to conditioning impressions that shape perception, behavior, and physiological response over time. In pharmacology, saṃskāra denotes deliberate refinement processes applied to substances themselves. Though these usages operate at different levels of embodiment, they share a common conceptual foundation: both refer to patterned change through repeated influence.

Preparations such as bhasmas (calcined mineral formulations), ghṛtas (medicated ghee), tailas (medicated oils), ariṣṭams (fermented decoctions), and rasāyanas (rejuvenative compounds) undergo elaborate, multi-stage processes—heating, cooling, incineration, trituration, fermentation, and repeated combination with specific media. These processes are not pharmaceutical conveniences; they are essential transformations that render substances biocompatible, non-toxic, and therapeutically directed (1,2,7).

Contemporary analyses have demonstrated that many bhasmas contain particles in the nano- and sub-nano range, with surface characteristics and biological interactions distinct from their raw precursors (14-16). From an Ayurvedic perspective, however, these findings represent correlates rather than explanations. Classical texts emphasize that saṃskāra alters not only chemical composition, but qualitative behavior—how a substance penetrates tissue, modulates vitality, and interfaces with perception and regulation (1, 2). Refinement, not force, is the hallmark of effective medicine.

Toward a Unified Continuum of Action – Temporal Dimension

When viewed through the lens of the kośas, both homeopathic and Ayurvedic medicines can be understood as acting at different depths of embodiment depending on their preparation. Crude substances tend to act primarily at the level of the Annamaya Kośa, influencing tissues and organs directly. Refined herbal preparations extend their influence into the Prāṇamaya Kośa, regulating vitality and physiological rhythm. More highly processed formulations—such as rasāyanas, bhasmas, and certain classical oils—are traditionally understood to reach into the Manomaya and Vijñānamaya Kośas, shaping perception, discernment, and long-term adaptive patterns (1, 3).

Homeopathic remedies, by virtue of potentization, act most directly at the causal–subtle interface, engaging the organizing intelligence of the vital force itself (4, 6). This does not collapse distinctions or eliminate material medicine. Rather, it clarifies their complementary roles. Different preparations are suited to different clinical situations, depending on where along the continuum disturbance predominates. Acute physical pathology may require material intervention to stabilize the organism. Chronic illness often demands deeper reorganization, initiated dynamically and supported materially.

A coherent integrative practice recognizes this continuum and selects interventions accordingly, honoring both the depth and the dignity of the living system it seeks to heal. Healing, therefore, is not a single corrective act but a gradual reorganization of the organism’s deepest regulatory tendencies—a process that unfolds along a continuum rather than through episodic intervention alone (4,5). This temporal dimension of cure is implicit in both Ayurvedic and homeopathic pharmacology, though articulated through different therapeutic grammars.

In Ayurveda, this logic is expressed through practices such as dinācaryā and the regulation of āhāra and vihāra. These were never conceived as adjunctive lifestyle recommendations, but as continuous therapeutic signals that entrain the organism toward coherence over time. Classical texts emphasize that chronic imbalance arises through repeated misalignment with natural rhythms, and therefore requires sustained, rhythmically aligned participation rather than isolated corrective measures (1,2). Therapeutic action, in this view, operates cumulatively, through consistency rather than intensity.

Hahnemann’s late development of the LM/Q potency scale reflects a strikingly parallel clinical realization. Having recognized that chronic disease represents a stabilized disturbance of the vital force rather than an episodic deviation, he concluded that cure requires gentle, repeated, and precisely regulated stimulation over time. In the sixth edition of the Organon, LM potencies are explicitly described as acting more deeply and durably when administered at regular intervals, allowing progressive reorganization of the vital force without overwhelming it (Organon §§246–248) (4). This stands in contrast to earlier centesimal prescribing strategies, which—while capable of profound action—were often administered episodically, reflecting an earlier stage in the clinical understanding of chronicity.

Seen together, dinācaryā and LM/Q prescribing express the same therapeutic insight: deeply conditioned patterns of imbalance are not undone through singular interventions, but through sustained, proportionate, and rhythmically appropriate engagement. Whether through daily practices that entrain regulatory order or through gently repeated homeopathic stimuli that guide the vital force toward coherence, healing proceeds as a process of gradual recalibration rather than abrupt correction.

Taken together, these traditions converge upon a shared principle: therapeutic refinement allows substances—whether materially present or not—to engage the organism through patterned interaction and resonance rather than gross biochemical dominance (12,17). In this sense, medicinal preparation and administration is not merely a technical process, but an ethical and ontological act, shaping how medicine meets life.

Conclusion: Medicine as Participation in Living Order

This inquiry has traced a shared medical logic running through Ayurveda and Homeopathy—one that understands health and disease not as isolated mechanical events, but as expressions of order and disorder within a living continuum. Across distinct historical, cultural, and methodological contexts, both systems converge upon a foundational insight: healing cannot be reduced to the manipulation of physical structures alone. It must engage the levels of organization at which life is patterned, regulated, and sustained over time.

By articulating the human being as a nested continuum of causal, subtle, and physical embodiment, Ayurveda provides a coherent ontological framework within which homeopathy’s dynamic principles can be coherently situated. Disease, in this view, does not originate in matter but crystallizes there. It begins as a disturbance of regulation—of vitality, perception, discernment and orientation—and only later becomes visible as physical pathology. The kośa and śarīra model does not function as metaphysical abstraction, but as a clinically relevant map of where imbalance arises and where therapeutic engagement must occur.

Within this framework, Hahnemann’s concept of the vital force assumes its proper depth and specificity. It is neither reducible to “energy” nor interchangeable with psychological process, but corresponds most closely to the regulatory intelligence operating at the interface of causal orientation and subtle discernment. Homeopathy’s emphasis on subjective experience, constitutional pattern, and the directionality of cure reflects a disciplined engagement with this level of life. Its remedies act not by force, but by resonance— eliciting reorganization at the level where coherence is first lost.

Hahnemann’s doctrine of chronic miasms extends this insight across time. His decisive recognition was that chronic illness persists not merely because symptoms recur, but because the organism has become conditioned toward particular modes of imbalance. Disease endures when maladaptive regulatory patterns are stabilized through repetition, suppression, or misalignment with natural rhythms. Here, Ayurveda offers a closely parallel understanding through the concepts of saṃskāra, karma (in its clinical sense), and nidāna parivarjana, emphasizing that unresolved patterns of adaptation imprint themselves within the subtle and causal domains unless consciously addressed.

Seen in this light, suppression is not simply a technical error; it is an ethical one. To silence symptoms without restoring regulation is to misunderstand the organism’s intelligence and to deepen disorder rather than resolve it. Both Ayurveda and homeopathy therefore reject domination as a therapeutic stance. Their shared alternative is refinement: working with life rather than against it, supporting the organism’s inherent capacity to reorganize itself toward coherence.

This ethic is expressed with particular clarity in their respective pharmacologies. Homeopathic potentization and Ayurvedic saṃskāra represent parallel recognitions that medicinal power is not determined by material quantity alone, but by the manner in which a substance engages the living system. Preparation is thus not ancillary, but central. Medicines are intentionally shaped to act at specific depths of embodiment—from tissue and vitality to perception, discernment, and causal orientation—allowing intervention to be matched precisely to the level and chronicity of disturbance present.

Crucially, both traditions also recognize that deep reorganization cannot occur through isolated acts alone. Chronic illness unfolds through time, and so must healing. Ayurvedic dinācaryā and the regulation of āhāra and vihāra reflect an ancient understanding that order is sustained through repeated, rhythmically aligned participation rather than episodic correction. Hahnemann’s later development of the LM/Q potency scale reflects an analogous clinical realization: that chronic disease requires gentle, sustained, and precisely regulated engagement over time, rather than intermittent intervention. In both systems, continuity, timing, and proportion prove as essential as depth.

The doctrine of obstacles to cure brings these insights into practical and moral focus. Hahnemann’s insistence that the physician must remove impediments arising from diet, lifestyle, environment, and habitual strain reveals an implicitly integrative vision of medicine— one that he clearly perceived, though could not fully operationalize within his historical context. Ayurveda fulfills this mandate by providing a comprehensive clinical system for stabilizing the terrain of the body, regulating daily and seasonal rhythm, refining perception, and aligning conduct with living order. In this way, Ayurveda does not merely complement homeopathy; it stabilizes and sustains the conditions under which homeopathic cure can unfold.

Taken together, these traditions articulate a medicine that is neither reductionist nor diffuse, neither purely material nor abstractly spiritual. They describe healing as a participatory process—one that unfolds through resonance, refinement, and ethical attention to life as it is actually lived. Cure, in this vision, is not the elimination of symptoms, but the restoration of coherence across depth, time, and meaning. Ayurveda and Homeopathy together offer not merely an integrative modality, but a reorientation of medicine itself: from control to coherence, from suppression to understanding, and from fragmentation to wholeness.

References

Sharma, R. K., & Dash, B. (2024). Caraka Saṃhitā (Vols. 1–7). Varanasi, India: Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office.

Suśruta. (2018). Suśruta Saṃhitā (K. K. Bhishagratna, Trans.). London, England: Forgotten Books.

Feuerstein, G. (2003). The deeper dimension of yoga: Theory and practice. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications.

Hahnemann, S. (2021). Organon of the Medical Art (6th ed., W.B. O’Reilly, Ed.; S. Decker, Trans.). Palo Alto, CA: Birdcage Press.

Hahnemann, S. (1999). The chronic diseases: Their peculiar nature and their homoeopathic cure (L. H. Tafel, Trans.). New Delhi, India: B. Jain Publishers.

Vithoulkas, G. (2014). The Science of Homeopathy (7th ed.). Greece: International Academy of Classical Homeopathy.

Mukherjee, P. K. (2010). Quality control of herbal drugs: An approach to evaluation of botanicals. New Delhi, India: Business Horizons.

Easwaran, E. (2007). The Upaniṣads. Canada: Nilgiri Press.

Dasgupta, S. N. (2024). A history of Indian philosophy (Vol. 1). New Delhi, India: Fingerprint Publishing.

Chikramane, P. S., Suresh, A. K., Bellare, J. R., & Kane, S. G. (2010). Extreme homeopathic dilutions retain starting materials: A nanoparticulate perspective. Homeopathy, 99(4), 231–242.

Chikramane, P. S., et al. (2012). Why extreme dilutions reach non-zero asymptotes: A nanoparticle perspective. Langmuir, 28(45), 15864–15875.

Rao, M. L., Roy, R., Bell, I. R., & Hoover, R. (2007). The defining role of structure in the plausibility of homeopathy. Homeopathy, 96(3), 175–182.

Elia, V., Napoli, E., & Germano, R. (2013). The memory of water: An almost deciphered enigma. In Dissipative Structures in Liquids. Springer.

Tripathi, Y. B., et al. (2010). Nanomedicine in Ayurveda: Bhasma as nanomedicine. Journal of Ayurveda and Integrative Medicine, 1(4), 282–289.

Chaudhary, A., & Singh, N. (2010). Herbo-mineral formulations of Ayurveda. Ancient Science of Life, 29(3), 18–26.

Mitra, A., et al. (2012). Characterization of Lauha Bhasma using advanced analytical tools. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge, 11(2), 285–290.

Bell, I. R., Koithan, M., & Brooks, A. J. (2013). Testing the nanoparticle–allostatic cross-adaptation hypothesis. Homeopathy, 102(1), 66–81.

Kent, J. T. (1900). Lectures on homoeopathic philosophy. New Delhi, India: B. Jain Publishers.

Burnett, J. C. (1891). Diseases of the liver. London, UK: Homoeopathic Publishing Company.

Bio:

Kirsten McGregor, CCH, AHC is a board-certified Classical Homeopath and Ayurvedic Health Counselor with an international clinical practice based in California. She is the founder of Metta Integrative Health and the Publisher and Co-Editor of The California Homeopath, a professional journal founded in 1882. Her scholarly and clinical work explores the thoughtful integration of Homeopathy and Ayurveda as a coherent continuum of care across foundational, regulatory, and physical domains of health, with particular emphasis on complex and chronic conditions. Her work is informed by years of advanced professional training in both Classical Homeopathy and Ayurvedic medicine, including full-time clinical education and ongoing practitioner-level study, grounding her integrative approach in depth, rigor, and lived clinical experience.

Kirsten McGregor, CCH, AHC

Website: https://www.mettaintegrativehealth.com

© 2026 Kirsten McGregor. All rights reserved.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

This license permits sharing with attribution for non-commercial purposes only. No adaptations, derivative works, or reuse of conceptual models, diagrams, or frameworks are permitted without the express written permission of the author.