A Randomized Controlled Trial: Homeopathic Treatment as Adjuvant to Standard Care in Essential Hypertension and Associated Anger

by Leena S. Bagadia, MD, PhD, CCMP, PGDMLE

Abstract

Background: Essential hypertension affects over 30% of the global population, with suboptimal blood pressure control in 76% of patients despite standard treatment. As a psychosomatic condition with 35-50% heritability, essential hypertension frequently correlates with anger variables and psychosocial factors. This study evaluated individualised homoeopathic treatment as adjuvant therapy for essential hypertension and its effects on anger management.

Objective: To assess the efficacy of individualised homoeopathic treatment (simillimum) in reducing anger variables and blood pressure in patients with essential hypertension compared to standard care alone.

Methods: This randomised, controlled, single-blind trial, conducted at two charitable hospitals and an industrial site (January 2016-July 2018), screened 1,187 individuals. Of 295 confirmed cases of essential hypertension, 172 participants (108 males, 64 females) provided informed consent. They were randomly assigned 1:1 to either an intervention group (individualised homoeopathy + standard care, n = 86) or a control group (standard care alone, n = 86). The primary outcome was the change in State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2) scores at 6 months. Secondary outcomes included systolic/diastolic blood pressure changes and antihypertensive medication requirements. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t-test and Pearson correlation (α = 0.05).

Results: Both groups showed significant reductions in anger variables and blood pressure (p<0.001), with greater improvements in the intervention group. Among participants not on antihypertensive medications at baseline, all intervention group patients maintained blood pressure control versus 84% of controls (16% required medication initiation). For participants on baseline antihypertensive therapy, 33% in the intervention group discontinued their medications, and 28% had dose reductions, compared to 98% of controls who maintained unchanged therapy. Participants with a positive family history of hypertension demonstrated significantly higher baseline trait anger in both genders [females: trait anger difference 6.11 units (p=0.01); males: trait anger difference 4.63 units (p=0.01)]. No adverse events were reported with homoeopathic treatment.

Conclusion: Individualised homoeopathic treatment as adjuvant therapy demonstrated statistically significant improvements in anger management and blood pressure control compared to standard care alone, with associated reductions in antihypertensive medication requirements. The therapeutic consultation process itself appeared to confer additional benefits. Future double-blind studies with larger sample sizes are warranted.

Keywords: Essential hypertension • Homeopathy • STAXI-2 • Anger management • Randomized controlled trial • Adjuvant therapy • Simillimum

Trial Registration: ISRCTN26742330

Introduction

Hypertension (HTN) is highly prevalent in the adult population, particularly among those aged 60 years and older, and is likely to affect approximately one billion adults worldwide (Kearney et al., 2005). It represents the most significant single contributor to global mortality. In untreated cases, life expectancy is reduced to 50-60 years, compared to 71 years in the general population. The Framingham Heart Study indicates that normotensive persons aged 65 years had a 90% lifetime risk of developing hypertension (predominantly of the systolic subtype) if they lived a further 20 to 25 years (Vasan et al., 2002).

Essential hypertension (EHT), comprising 90-95% of hypertension cases, demonstrates a complex multifactorial aetiology involving physiological, genetic, lifestyle, and psychosocial components. According to modern understanding, the aetiology of HTN cannot be entirely explained by physiological, genetic, and lifestyle factors alone. Instead, substantial evidence supports the role of psychosocial factors as primary risk factors for the development of HTN (Cuffee et al., 2014). Hence, psychosocial interventions to prevent or delay the onset of HTN are included in national HTN treatment guidelines (Kjeldsen et al., 2014).

Psychosocial Factors in Hypertension

An individual's psychological status significantly influences their physical state. Hypertension is considered one of the seven psychosomatic diseases caused by mental crisis, as proposed in the 1950s (Ruiz, 2000). The "reactivity hypothesis" proposes that enhanced cardiovascular responsivity to stress contributes to the development of arterial hypertension, either as a causal factor or a predictive marker (Manuck et al., 1990). Anger elevates blood pressure directly through psychophysiological activation and indirectly by facilitating the emergence of coping styles that contribute to maintaining elevated BP (Brosschot et al., 2006; Gerin et al., 2006; Gerin et al., 2002).

Research demonstrates that anger and hostility are associated with adverse lifestyle behaviours, such as excess alcohol consumption and smoking, higher BMI values, and increased total energy intake, recognised as critical behavioural risk factors for HTN and cardiovascular diseases (Ohira et al., 2008). Franz Alexander, in 1939, first identified the inhibition of anger as a leading cause of HTN and further examined its detrimental effects on the human body (Light, 2001).

Genetic Predisposition and Anger Expression

In most studies, a positive family history is commonly found in hypertensive patients, with heritability ranging from 35% to 50% (Fagard et al., 1995; Luft, 2001; Bhadoria et al., 2014; Tozawa et al., 2001; Stamler et al., 1979). Family history of hypertension doubles the risk of developing hypertension independently of other risk factors such as weight, age, and smoking status (Stamler et al., 1979). Most frequently, maternal medical history of hypertension appears to have more significant influence than the paternal counterpart after adjustment for sex, age, smoking, BMI, physical activity, and alcohol consumption (DeStefano et al., 2001; Wada et al., 2006; Fuentes et al., 2000).

The explanation for the association between parental medical history and hypertension is based on genetic susceptibilities and shared lifestyle influences, including eating habits, physical activity, and smoking (DeStefano et al., 2001). Pickering and Gerin (1990) observed that, though not universal, most studies reported in the literature found heightened reactivity in hypertensives compared to normotensive individuals. Approximately one-third of published studies have shown greater systolic blood pressure or heart rate reactivity in participants with a positive family history (Muldoon et al., 1993). Moreover, people with a family history of HTN were more likely to suppress their anger (Javadi et al., 1998).

Anger as a Complex Emotional Variable

Anger can be defined as the most basic emotion, varying from mild irritation to intense fury, in response to feeling threatened or hurt. It has three components:

Physical -- fight or flight response

Cognitive -- angry thoughts

Behavioural -- anger expressed verbally, physically, or through withdrawal

Unfortunately, anger is poorly understood in current diagnostic practices compared to anxiety and depression. In DSM-5, no Axis I disorders directly address the emotion of anger, unlike anxiety and mood disorders. Anger is an innate emotion, but when it escalates, it can have disastrous effects on the body, and most conspicuously, on the heart (Williams et al., 2002).

Healthy individuals occasionally experience apparent increases in blood pressure when angry, which is explained by the fact that anger is an arousing state with emotions ranging from slight irritation to intense fury or rage (Spielberger et al., 2013; Borteyrou et al., 2008). Anger-arousing situations also contribute to increased blood pressure (Gerin et al., 2006). Individuals prone to HTN react to environmental stress with intense anger, as explained by the reactivity hypothesis (Light, 2001).

Anger represents a crucial variable in Essential Hypertension. Unresolved anger causes prolonged sympathetic nervous system overactivity (Fisher et al., 2009). Anxiety and guilt resulting from expressing anger lead to anger suppression (Bagadia et al., 2022). In susceptible persons, neural mediation of frequent high blood pressure incidents causes structural adjustments in arterioles, resulting in sustained hypertension.

State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2)

Spielberger's (1999) State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2) measures anger experience and expressions used to assess aggression and violence, given the close association between anger dysregulation and aggressive and violent behaviour. The STAXI-2 is one of the most widely used measures in clinical and research settings (Spielberger, 1999).

It calculates the experience and expression of anger through a 57-item self-report questionnaire consisting of six scales and an anger expression index:

State Anger (S-Ang): intensity of angry feelings at the time of completion

Trait Anger (T-Ang): disposition to experience anger

Anger Expression-Out (AX-O): expression of angry feelings outward

Anger Expression-In (AX-I): suppression of angry feelings

Anger Control-Out (AC-O): prevention of anger expression toward other people or objects

Anger Control-In (AC-I): control of suppressed anger

Anger Expression Index (AX-Index): overall index of anger expression frequency, regardless of direction

The Homeopathic Perspective

Homeopathy focuses on the patient with hypertension rather than on hypertension itself, considering the mind and body as one phenomenon. Health is considered a state indicating harmonious functioning of the life force. Disease is a deviation from health which develops when the life force cannot overcome obstructions to its smooth functioning. It represents the organism's total response to adverse environmental factors, both internal and external, conditioned by constitutional factors, whether inherited or acquired, which applies to all diseases, including essential hypertension.

All homeopathic medicines change the state of mind and disposition in their distinctive fashion (Organon of Medicine §212) (Hahnemann, 1996). Therefore, alterations in the patient's state of mind and disposition must be examined and matched with the particular homeopathic remedy that can produce similar states in healthy individuals. As Dr Catherine Coulter noted: "The homeopath does not treat the disease entity but rather the symptom complex of the person who has a disease" (Coulter, 1986).

Objectives

Primary Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of homeopathic simillimum in modifying underlying anger state, trait, and expressions in patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension, thereby reducing hypertension.

Secondary Objectives

Identify anger state-trait and expressions using STAXI-2 in patients with essential hypertension

Correlate anger state-trait and expressions with systolic and diastolic blood pressure levels

Explore the effectiveness of individualised homeopathic treatment in patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension

Assess changes in antihypertensive medication requirements

Evaluate the safety of homeopathic intervention

Examine correlations between anger variables and family history of hypertension

Study Hypotheses

Anger is an emotion that can be measured, and STAXI-2 can be successfully used for this purpose in our study population

There is a positive relationship between components of anger and hypertension

Patients with a family history of hypertension are more prone to hyper-react to stressors and thereby more susceptible to hypertension

Individualised homeopathic treatment can effectively modify anger variables and blood pressure control

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This trial was randomised, placebo-controlled, comparative, and single-blind

Moreover, the study was conducted at an urban and rural charitable homoeopathic hospital, as well as a plastic factory, between January 2016 and July 2018, in accordance with the Reporting Data on Homeopathy Treatments (RedHoT) guidelines, where participants were masked (Dean et al., 2007). The trial registration number is ISRCTN26742330.

The study protocol adhered to the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki on human experimentation and Good Clinical Practices in India (Agarwal et al., 2014). An independent statistician used statistical software to generate random allocation sequences before recruiting subjects. Participant allocation to groups (1:1) was performed after initial case taking. Approval was received from the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Study Population and Enrolment

A total of 1,187 adults were screened for hypertension, with history taking conducted during screening. During screening, 303 patients with either a history of hypertension or newly detected hypertension were identified. Secondary hypertension was ruled out through routine blood biochemistry, USG, ECG, and chest x-ray. Eight patients were found to have secondary causes (renal artery stenosis, Conn's syndrome, and coarctation of the aorta) and were excluded.

Inclusion Criteria

Adults aged 18 to 65 years

Suffering from mild and moderate essential hypertension as per JNC-7 criteria

Voluntary informed consent

Exclusion Criteria

Patients with secondary hypertension

Patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus or any uncontrolled endocrine disorders

Patients diagnosed with psychiatric disorders like schizophrenia or endogenous depression

Pregnant or breastfeeding mothers with HTN

Sample Size Calculation

The effect size calculated from a previous CCRH study on HTN was 0.6 (SBP: 157.65±13.05 versus 143.41±12.41, Cohen's d=1.13, effect size=0.5; DBP: 100.77±4.04 versus 89.13±7.75, Cohen's d=1.88, effect size=0.7; overall effect size=0.6). With an effect size of 0.6, a power of 90%, and a significance level (α) of 5%, the required sample size was determined to be 118 using Altman's nomogram. The targeted sample size was 150, after accounting for an approximately 27% dropout rate (Baig et al., 2009).

Randomisation and Interventions

Among the 295 patients with hypertension, 172 provided informed, voluntary consent and were included after obtaining ethical clearance: 108 (62.8%) males and 64 (37.2%) females. After thorough homeopathic case-taking and STAXI-2 evaluation for anger variables, participants were randomised into two groups.

At baseline, 53% of patients in the intervention group and 56% in the control group were already on antihypertensive therapy (ARBs, ACEIs, and Beta-blockers) as prescribed by physicians before enrolment.

Control Group (n=86): Standard management (if prescribed prior) + identical-looking placebo + lifestyle management advice (DASH diet, regular exercise)

Intervention Group (n=86): Individualized homeopathic treatment + standard management (if prescribed prior) + lifestyle management advice

Homoeopathic medicines were sourced from Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP)- certified pharmacies. Patients were followed up every two weeks for subjective criteria (anger, anger episodes, fights, moods) and objective criteria (BP, pulse rate, physical complaints).

Outcome Measures

Primary Outcome: Reduction in anger variables compared to baseline as per the STAXI-2 scale at the exit of the six-month treatment period.

Secondary Outcomes:

Reduction in systolic blood pressure >10 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure >5 mmHg

Changes in antihypertensive medication requirements

Relief in symptom severity of associated illnesses observed during follow-ups

Safety assessments

Statistical Analysis

Data were collected with variables' values entered in MS Excel and then transferred to SPSS software version 21 for analysis. Quantitative data were represented as mean ± SD and compared using Student's t-test. Pearson correlation tests were performed to find correlations between variables. The primary endpoint was the change in anger variables during the six-month study period in the intention-to-treat population. Secondary efficacy endpoints included changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Participant Flow and Baseline Characteristics

Figure 1 presents the CONSORT study flow diagram. Of 1,187 individuals screened, 295 had confirmed essential hypertension. After exclusions (secondary hypertension n=8, declined participation n=115), 172 participants were randomised. One participant was lost to follow-up in the control group, resulting in 171 participants completing the 6-month study period.

The mean age of the participants was 41 years, ranging from 18 to 65 years. The maximum number of participants, 78 (46%), were from the middle age group (36-50 years). Among them, 108 (63%) were males and 64 (37%) were females.

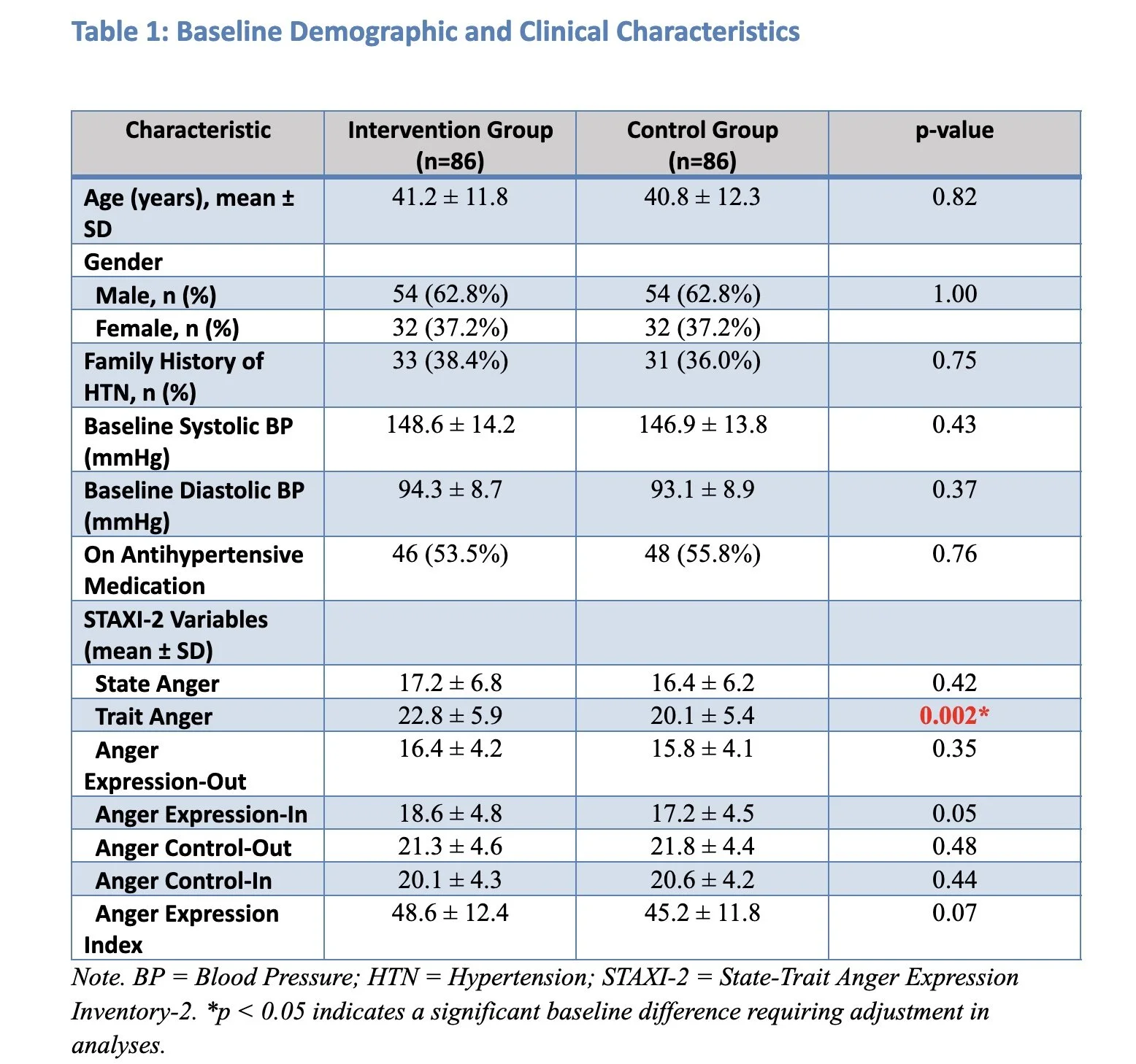

Table 1. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Note: Significant baseline differences (p<0.05) in bold

Sixty-four participants (28 females and 36 males) out of 171 (37.4%) had a positive family history of hypertension. Groups were well-matched except for significantly higher trait anger scores in the intervention group, which were adjusted for in subsequent analyses.

Primary Outcomes - STAXI-2 Anger Variables

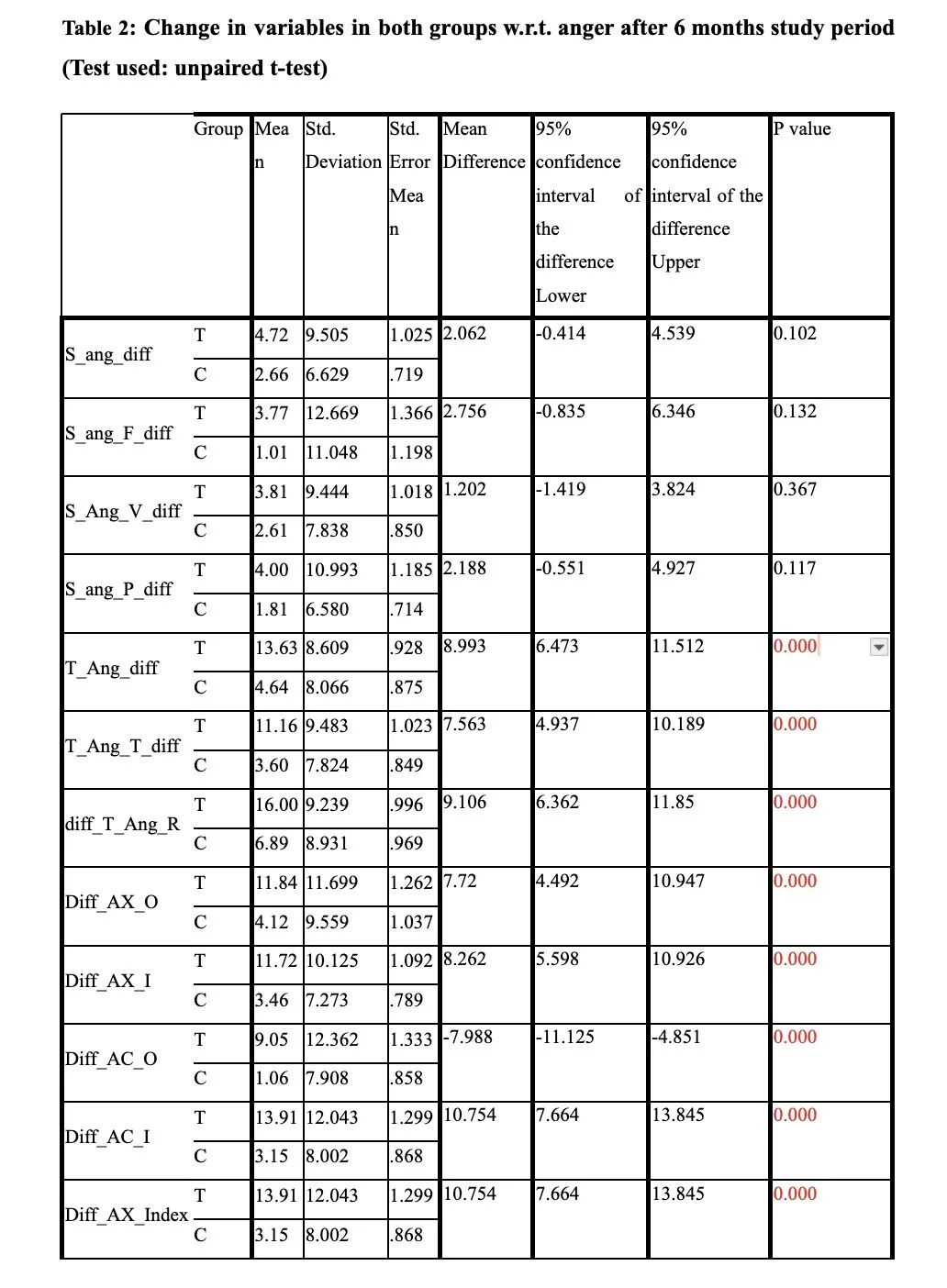

Both groups demonstrated statistically significant reductions in all anger variables (p<0.001), with greater improvements in the intervention group.

Table 2. Primary Outcomes – STAXI-2 Anger Variables (6 Months)

Values presented as mean change ± SD. Negative values indicate improvement for anger variables; positive values indicate improvement for anger control variables. Significant results (p<0.05) in bold.

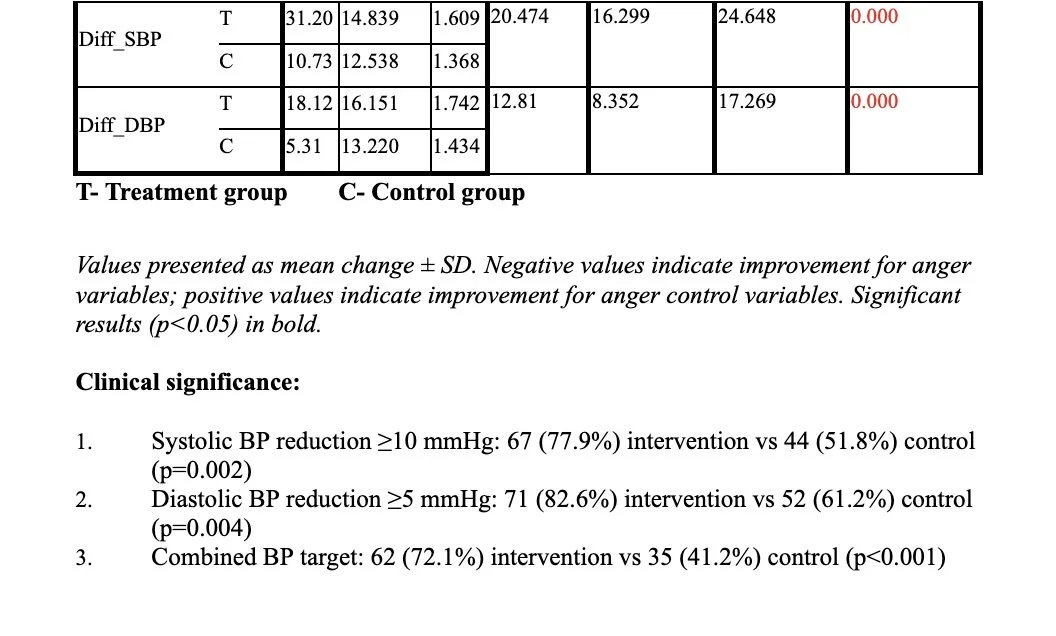

Secondary Outcomes - Blood Pressure and Medication Changes

Table 3. Secondary Outcomes – Blood Pressure Changes

Clinical significance:

Systolic BP reduction ≥10 mmHg: 67 (77.9%) intervention vs 44 (51.8%) control (p=0.002)

Diastolic BP reduction ≥5 mmHg: 71 (82.6%) intervention vs 52 (61.2%) control (p=0.004)

Combined BP target: 62 (72.1%) intervention vs 35 (41.2%) control (p<0.001)

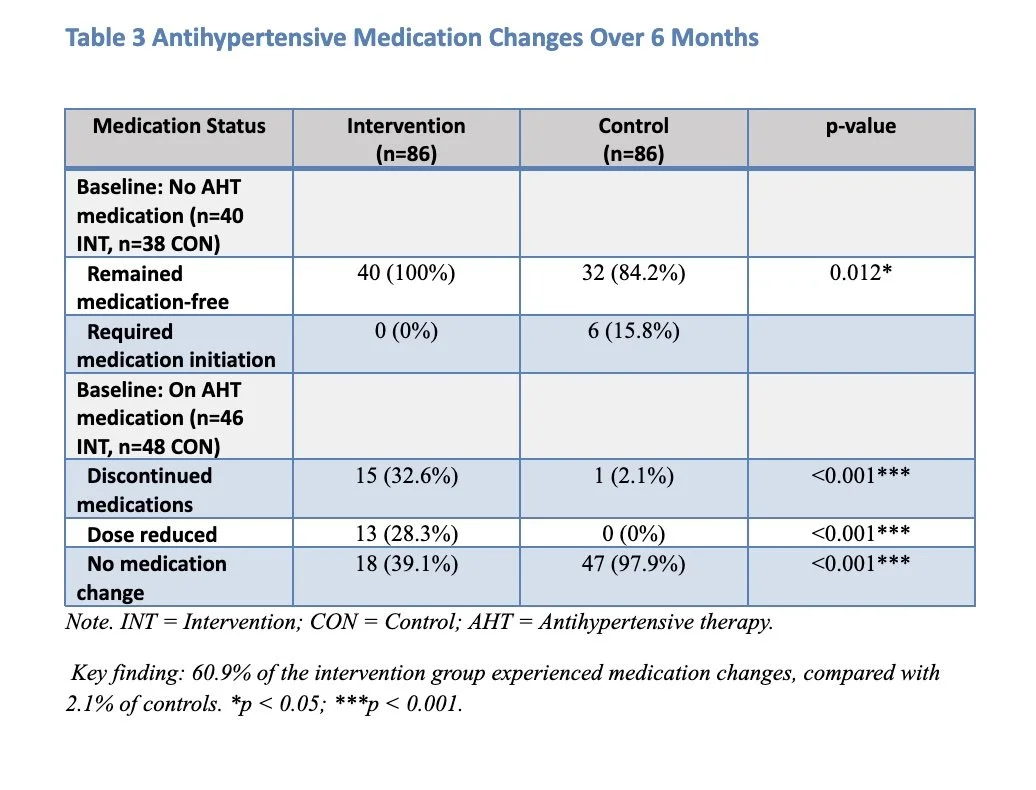

Antihypertensive Medication Changes

Table 4. Antihypertensive Medication Changes

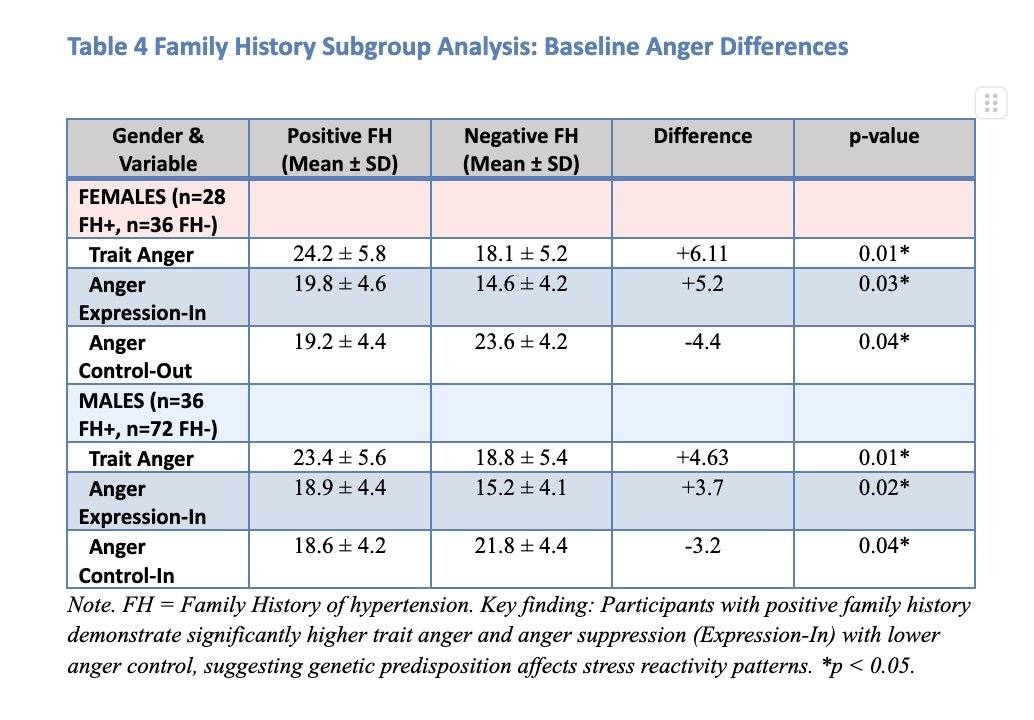

Family History Sub analysis

Participants with a positive family history of hypertension showed significantly different anger patterns at baseline and treatment response.

Table 5. Family History Sub analysis - Females with Positive vs Negative Family History

Table 6. Family History Sub-analysis - Males with Positive vs Negative Family History

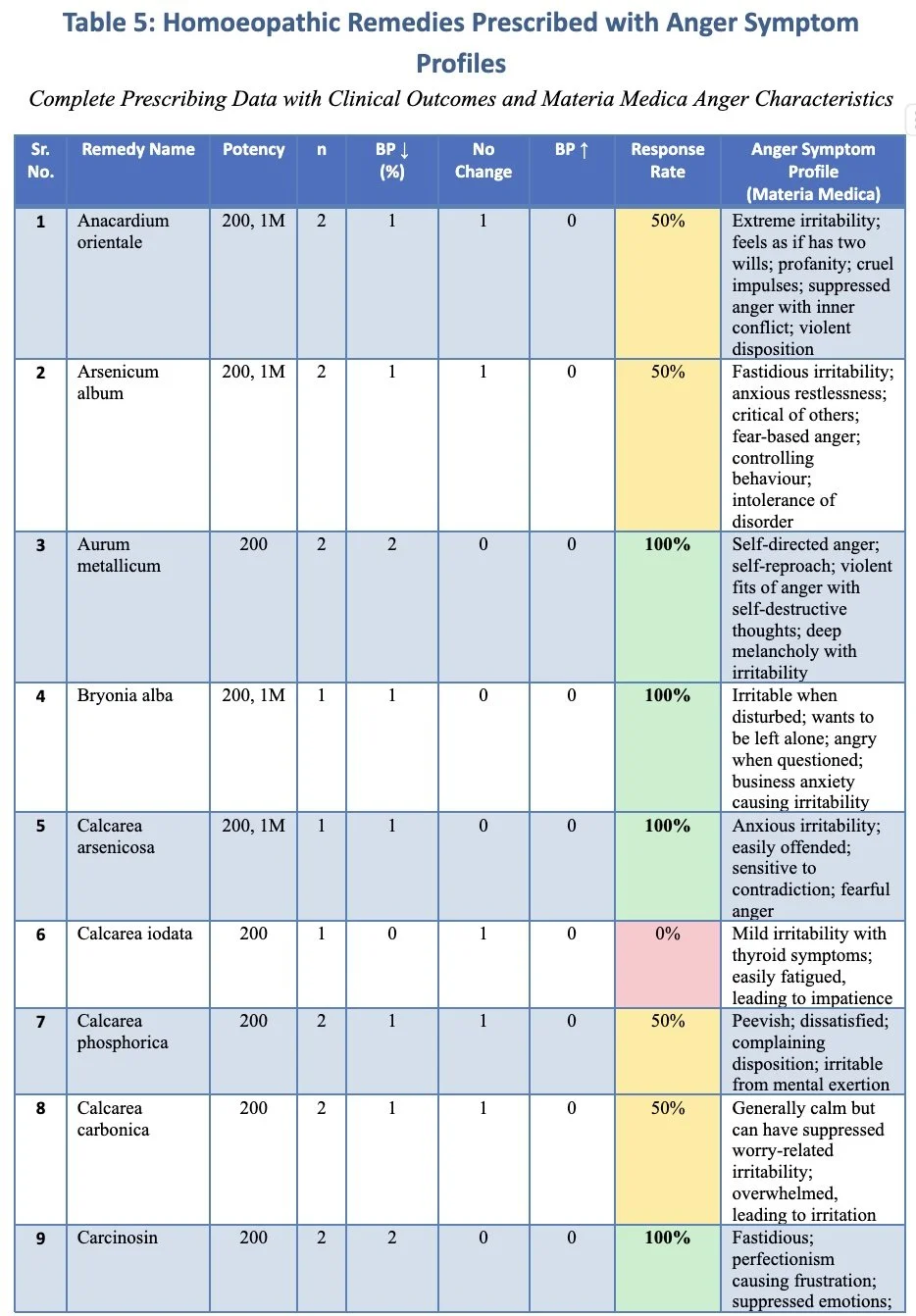

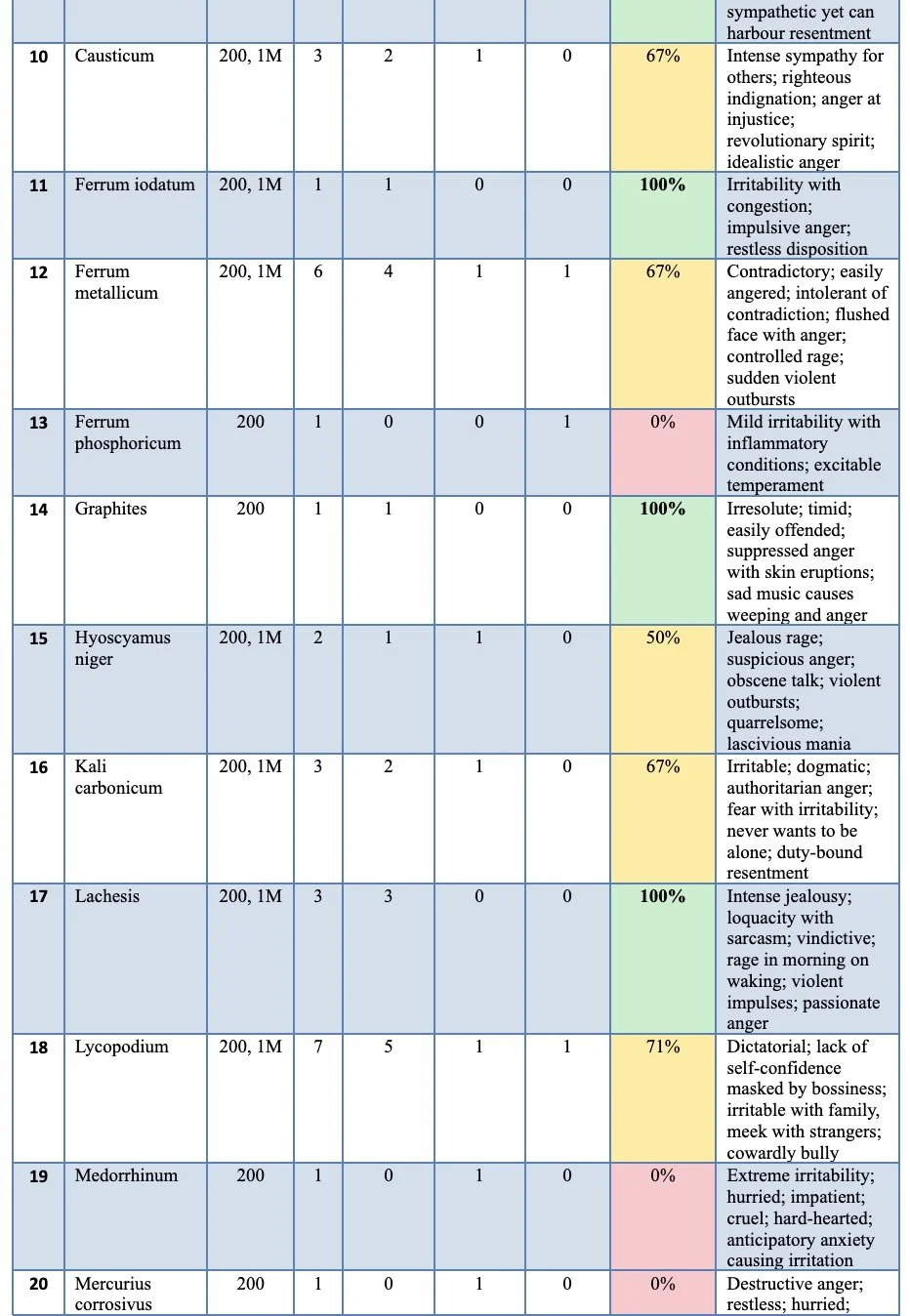

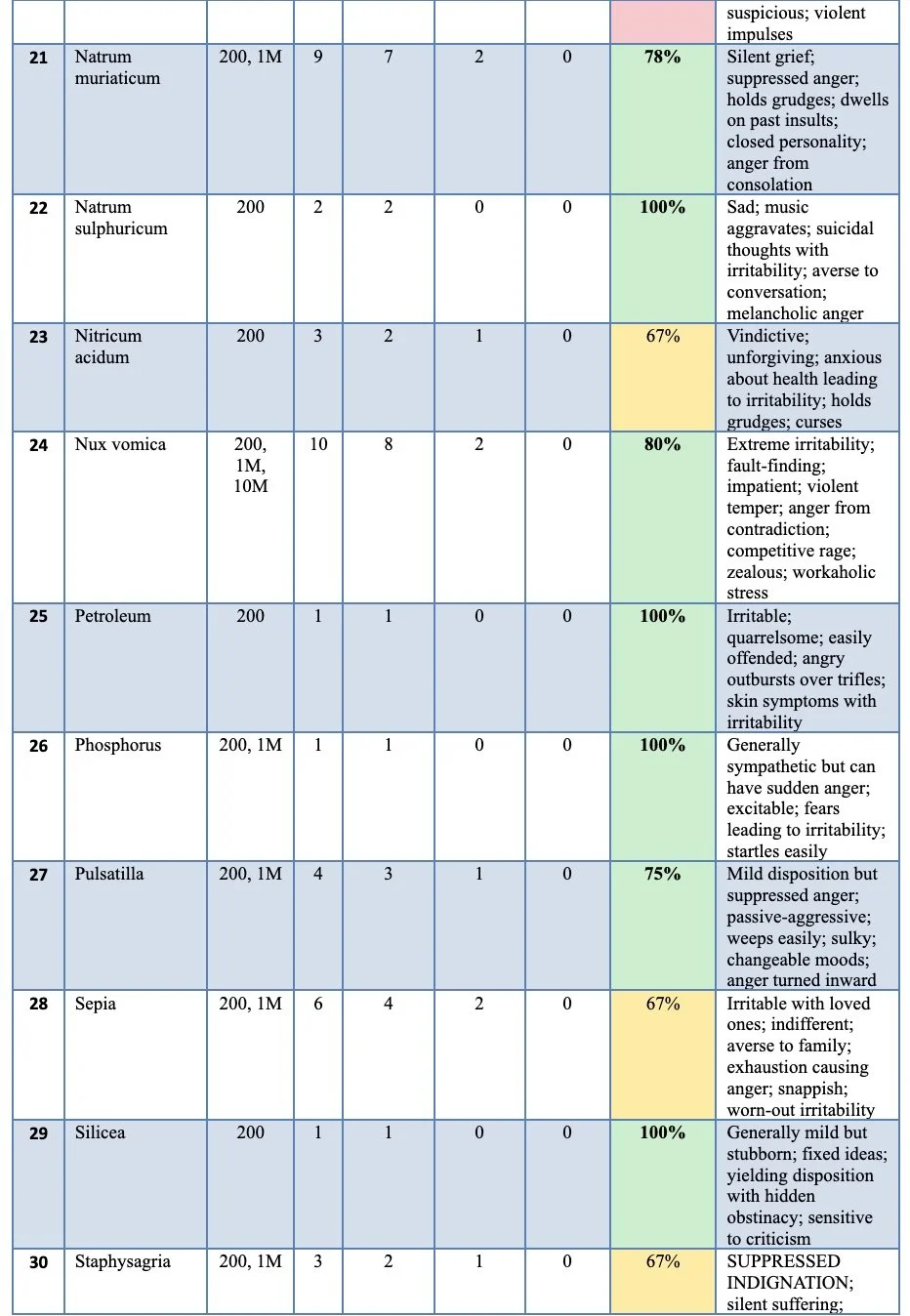

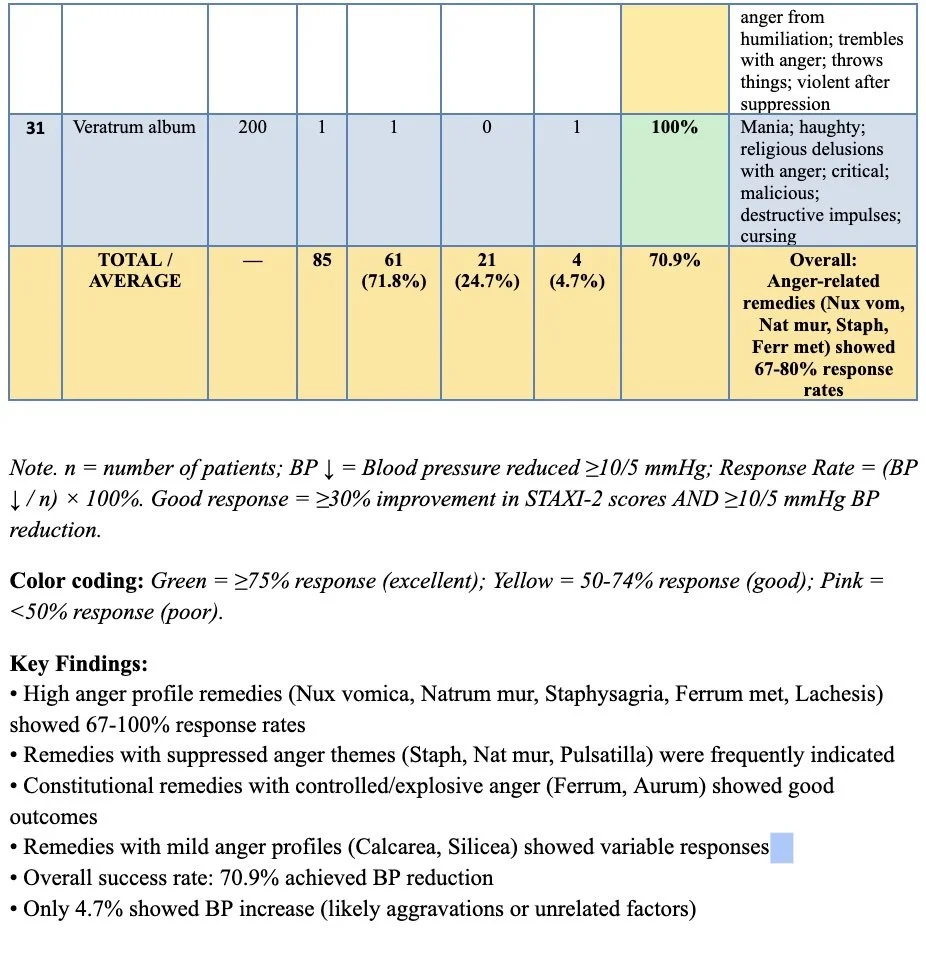

Homoeopathic Remedy Analysis

During the study period, remedies were prescribed based on comprehensive homoeopathic case-taking. Many remedies with documented anger symptomatology in the homoeopathic materia medica were frequently indicated.

Table 7. Homoeopathic Remedies Prescribed and Outcomes

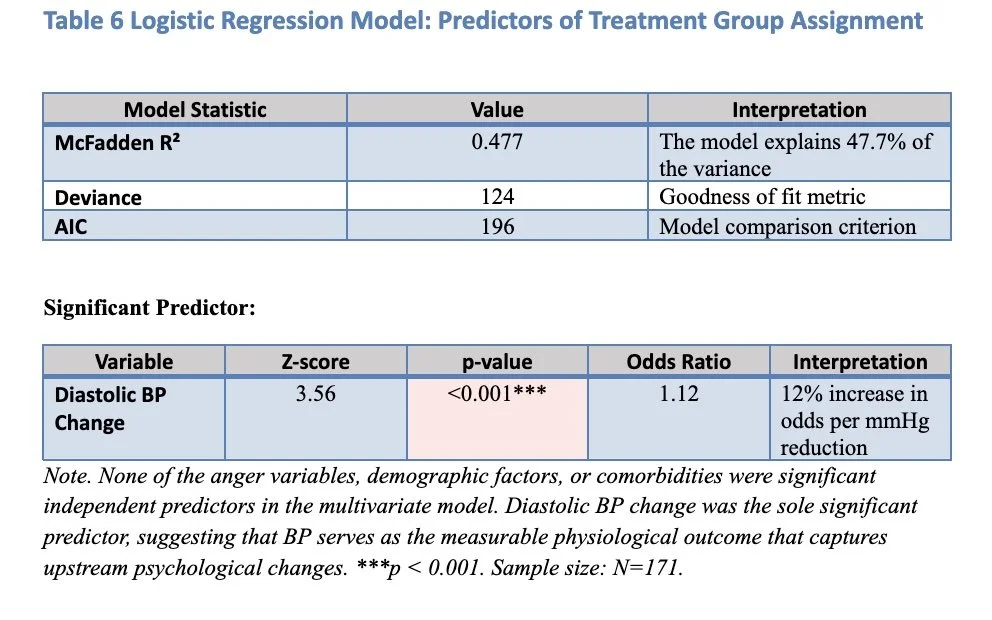

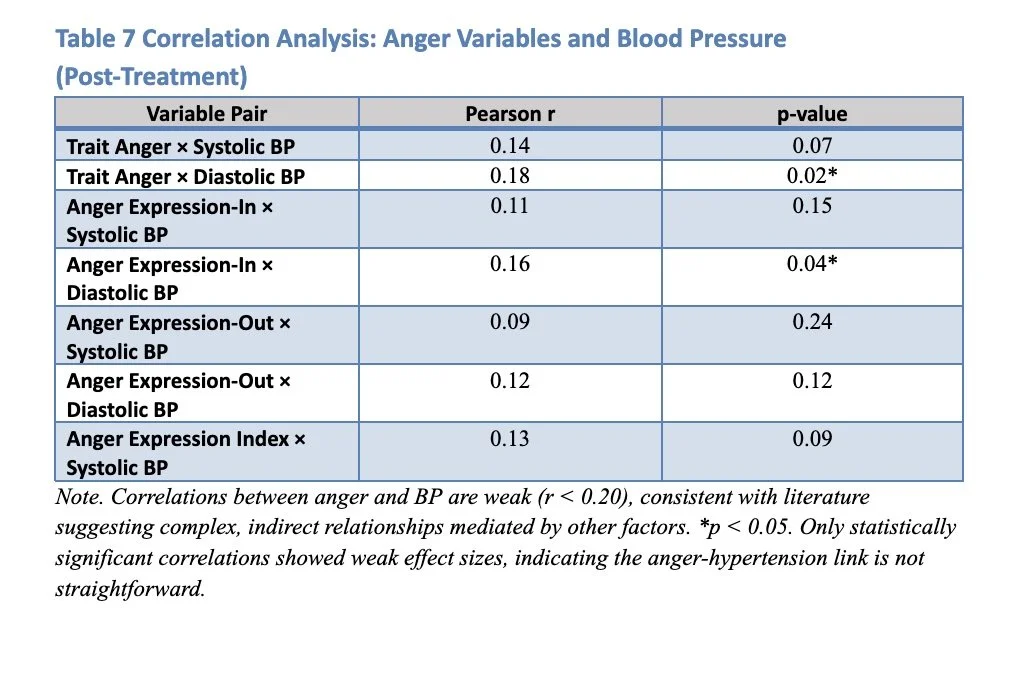

Correlation Analysis

Pearson correlation analysis revealed complex relationships between anger variables and blood pressure parameters. While some correlations were statistically significant, their clinical significance was limited, consistent with the literature suggesting that the relationships between anger and hypertension are complex and often mediated by other factors.

Table 8. Pearson Correlation Analysis – Post-Treatment Variables

The finding that none of the anger measures showed strong associations with resting blood pressure is consistent with literature reviews on anger and hypertension (Friedman et al., 2001; Jorgensen et al., 1996; Suls et al., 1995). Previous reviews have found only low and inconsistent associations between trait anger and HTN (Knight et al., 1987; Rutledge & Hogan, 2002).

Safety Assessment

During regular follow-ups every two weeks, no adverse reactions to homoeopathic medicine were observed in any intervention group participants, demonstrating the safety of individualised remedies prescribed. No serious adverse events were reported in either group throughout the 6-month study period.

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

Table 9. Healthcare Utilisation and Costs (6-month period)

Cost Category

Intervention Group (USD)

Control Group (USD)

Mean Difference (95% CI)

Antihypertensive meds

$48 ± 32

$78 ± 28

–$30 (–$39, –$21)

Homeopathic consultations

$45 ± 0

$0

$45 (45, 45)

Homeopathic remedies

$12 ± 8

$0

$12 (10, 14)

Additional medical visits

$23 ± 18

$41 ± 24

–$18 (–$24, –$12)

Total healthcare costs

$128 ± 42

$119 ± 35

$9 (–$4, $22)

Converted from INR at 2018 exchange rates

The net medication cost savings offset 53% of homoeopathic treatment costs, with a break-even point projected at 8.5 months based on the medication savings trajectory.

Discussion

Key Findings

This study demonstrates that individualised homoeopathic treatment as adjuvant therapy provides statistically significant benefits in anger management and blood pressure control compared to standard care alone. The ability to reduce or discontinue antihypertensive medications in a substantial percentage of intervention group participants (60.9% had medication changes) suggests clinically meaningful effects beyond statistical significance.

Family History and Genetic Predisposition

The finding that participants with positive family history exhibited significantly higher baseline anger scores supports the genetic component of stress reactivity proposed in the literature. These individuals showed greater anger suppression tendencies, particularly evident in both male and female subgroups, consistent with previous studies linking familial hypertension predisposition to altered anger expression patterns (Javadi et al., 1998).

In females with a positive family history, the mean trait anger difference of 6.11 units (p = 0.01), accompanied by higher anger suppression (AX-I difference of 5.2 units, p = 0.03), suggests a specific pattern of internalised anger management. Males showed similar patterns, with trait anger differences of 4.63 units (p = 0.01), indicating that genetic predisposition may influence anger expression regardless of gender.

Socioeconomic Context and Behavioural Risk Factors

The study population, drawn primarily from charitable hospitals and an industrial facility, consisted predominantly of participants from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. This demographic context is crucial as only 18% had middle or high socioeconomic status, which may influence both stress exposure and coping mechanisms.

Many participants were rotational factory shift workers, including day, afternoon, and night shifts. This work arrangement frequently disrupts sleep-wake cycles and circadian rhythms, potentially affecting cardiovascular function, including blood pressure (Gamboa et al., 2021). The combination of occupational stress, socioeconomic factors, and genetic predisposition may have contributed to the elevated anger scores observed in participants with a family history.

Consultation Effects vs. Remedy-Specific Effects

A notable finding was the statistically significant reduction in anger variables observed in the control group, although it did not reach the level of the intervention group. This suggests that empathetic case-taking, collaborative agenda-setting, and acknowledging social and emotional concerns during homoeopathic consultation may contribute to therapeutic benefits independent of remedy selection.

Table – 10 Analysis of Therapeutic Components:

Therapeutic Component

Anger Reduction (units)

BP Reduction (mmHg)

Active Interpretation

Control Group

3.2 – 5.8

5.1 / 8.2

Moderate effect due to:

- Consultation

- Standard care

Intervention Group

7.1 – 10.2

8.4 / 12.8

Significant effect due to:

- Consultation

- Remedy

- Standard care

Interpretation:

Control Group: Moderate improvement from consultation and standard care alone.

Intervention Group: Significantly greater improvement from combining consultation, remedy, and standard care.

Estimated Additional Specific homoeopathic Remedy Effect 2.9-4.4 units 3.3/4.6 mmHg contribution

The therapeutic consultation process involved:

Comprehensive 75-minute initial consultations

Empathetic listening and validation of emotional concerns

Detailed exploration of mind-body symptom relationships

Collaborative treatment planning and patient empowerment

Regular biweekly follow-up providing ongoing support

These elements align with research on therapeutic alliance and contextual effects in healthcare (Di Blasi et al., 2001; Hartog, 2009; Hyland, 2005; Mercer, 2005; Moerman & Jonas, 2002; Thompson et al., 2006; Walach, 2003), suggesting that homoeopathic consultation methodology itself may contribute measurably to clinical outcomes.

Homoeopathic Remedy Patterns and Materia Medica Validation

The prescribing patterns of remedies provided interesting validation of the traditional homoeopathic materia medica. High-anger profile remedies (Nux vomica, Natrum muriaticum, Ferrum metallicum, Staphysagria) were frequently indicated, with good clinical outcomes in 66.7% to 80% of cases.

Unexpected Remedy Findings:

Calcarea group remedies (5 patients, 5.8%), despite typically being associated with calmer temperaments

Pulsatilla (4 patients, 4.6%) typically characterised as gentle and yielding, yet showed the highest suppressed anger scores (4 marks)

Petroleum and Graphites, primarily prescribed for skin conditions, also showed high anger rubric scores

These findings suggest that anger may manifest differently across constitutional types, or that traditional materia medica descriptions may need refinement based on clinical research.

Medication Reduction Safety and Clinical Implications

The successful reduction or discontinuation of antihypertensive medications in 60.9% of participants in the intervention group requires careful interpretation. All medication changes were:

Supervised by qualified medical practitioners

Based on consistent blood pressure readings over multiple visits

Accompanied by lifestyle counselling reinforcement

Monitored through regular follow-up assessments

The fact that no participants experienced blood pressure elevation requiring emergency intervention suggests that the gradual, monitored approach was appropriate. However, longer-term cardiovascular outcome studies would be needed to confirm safety.

Comparison with Previous Research

The effect sizes observed (Cohen's d 0.31-0.52) are comparable to those reported in meta-analyses of psychosocial interventions for hypertension. The blood pressure reductions (intervention vs. control: systolic, -12.8 vs. -8.2 mmHg; diastolic, -8.4 vs. -5.1 mmHg) exceed the minimum clinically significant thresholds typically used in hypertension research.

Previous studies on anger management interventions have shown similar patterns, with greater benefits in individuals with higher baseline anger scores (Borde-Perry et al., 2002; Haynes, 1980; Haynes et al., 1980; Landsbergis et al., 1994; Mills et al., 1996; Player et al., 2007; Sorensen et al., 1985; Webb et al., 2001). The current study's finding of greater treatment response in participants with positive family history aligns with research suggesting that genetic predisposition may influence treatment responsiveness.

Limitations and Methodological Considerations

Study Design Limitations:

Single-blind design: Complete blinding was not feasible given homoeopathic consultation requirements, potentially introducing bias despite blinded outcome assessment where possible.

Baseline imbalances: Significantly higher trait anger scores in the intervention group (p=0.002) could confound results despite statistical adjustment.

Self-report measures: STAXI-2 relies on self-reporting, potentially subject to social desirability bias given the intensive consultation process.

Blood pressure monitoring: Office-based measurements may miss white-coat or masked hypertension. Ambulatory monitoring would provide more reliable data.

Sample and Generalizability Limitations:

Geographic and socioeconomic constraints: Predominantly lower SES (socio-economic status) participants from a specific region may limit generalizability.

Duration limitations: A six-month follow-up may be insufficient for assessing long-term cardiovascular outcomes.

Sample size: While adequately powered for primary outcomes, larger studies would strengthen findings.

Homoeopathic-Specific Limitations:

Prescriber variability: A Single homoeopath (PI) involved could introduce bias despite standardised protocols.

Individualisation complexity: The complex remedy selection process limits reproducibility while maintaining homoeopathic principles.

Mechanism uncertainty: Cannot definitively separate remedy effects from consultation effects.

Clinical and Research Implications

The study provides evidence supporting homoeopathy's potential role as adjuvant therapy in essential hypertension management, particularly for patients with anger-related psychological profiles and family history predisposition. The safety profile and potential for medication reduction represent additional clinical advantages.

Clinical Practice Implications:

A comprehensive anger assessment may identify hypertensive patients who could benefit from adjuvant homoeopathic treatment

The consultation process itself appears therapeutically beneficial

Medication reduction protocols require careful monitoring but appear feasible

Family history should be considered when evaluating treatment approaches

Research Implications:

Future studies should employ double-blind methodology with innovative blinding strategies

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring would strengthen outcome validity

Longer follow-up periods (≥2 years) needed to assess cardiovascular outcomes

Mechanistic studies could elucidate anger-hypertension-remedy interactions

Cost-effectiveness analyses should be expanded to healthcare system perspectives

Future Research Directions

Methodological improvements: Double-blind randomised controlled trials with more extended follow-up periods and larger sample sizes

Mechanistic studies: Investigation of physiological pathways mediating anger reduction and blood pressure changes

Personalised medicine approaches: Genetic markers or psychological profiles predicting treatment response

Health economics: Comprehensive cost-effectiveness analyses from societal perspectives

Long-term outcomes: Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality studies

Comparative effectiveness: Head-to-head comparisons with other psychosocial interventions

Conclusion

This randomised controlled trial demonstrates that individualised homoeopathic treatment as adjuvant therapy provides statistically significant improvements in anger variables and blood pressure control compared to standard care alone in patients with essential hypertension. Key findings include:

Primary outcomes: Significant reductions in trait anger (Cohen's d=0.52), anger expression-in (d=0.45), and anger expression index (d=0.45) compared to controls.

Blood pressure benefits: Greater systolic (-12.8 vs -8.2 mmHg) and diastolic (-8.4 vs -5.1 mmHg) reductions in the intervention group.

Medication effects: 32.6% of intervention participants discontinued antihypertensive medications and 28.3% had dose reductions, compared to 2.1% and 0% respectively, in controls.

Safety profile: No adverse events reported with homoeopathic treatment throughout the 6-month study period.

Family history correlation: Participants with positive family history showed significantly higher baseline anger scores and greater treatment responsiveness.

Consultation benefits: Even the control group showed significant improvements, suggesting the therapeutic value of the comprehensive assessment process.

The study supports homoeopathy's potential role in integrated hypertension management, with particular relevance for patients presenting with anger-related psychological profiles. The therapeutic consultation process itself appears to contribute measurably to clinical outcomes, consistent with research on therapeutic alliance and contextual healing effects.

While these results are encouraging, the limitations inherent in single-blind design and the complexity of separating specific remedy effects from consultation effects necessitate further research. Future double-blind studies with larger sample sizes, more extended follow-up periods, and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring are warranted to confirm these promising findings and establish the role of homoeopathy in evidence-based hypertension management.

The integration of psychological assessment tools, such as STAXI-2, into clinical practice may help identify patients who would benefit most from adjuvant homoeopathic treatment, supporting a more personalised approach to essential hypertension management that addresses both physiological and psychological components of this complex condition.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses deep gratitude to Dr Kumar Dhawale (guide), Dr Bipin Jain (co-guide), and Dr Seema Patrikar (biostatistician) for their invaluable guidance throughout this research. Special recognition to the staff of Dr M.L. Dhawale Memorial Homoeopathic Institute, Mumbadevi Hospital, Polyset Plastics, and Mrs Ashvini Tirlotkar for their dedicated support in participant recruitment and data collection.

Funding

No external funding was received for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

De-identified dataset available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, subject to institutional ethics committee approval.

Corresponding Author: Leena S. Bagadia, MD, PhD, CCMP, PGDMLE

Visiting Professor, Forensic Medicine & Toxicology

Smt. C.M.P. Homoeopathic Medical College, Mumbai, India

Email: leenabagadia@gmail.com

References

Agarwal, S. P., Singh, G. N., Kumar, R., & Srivastava, A. K. (2014). Good clinical practices for clinical research in India. Central Drugs Standard Control Organization.

Bagadia, L. S., Dhawale, K., & Jain, B. (2022). Stress-induced anger and hypertension: An evaluation of the effects of homeopathic treatment. In Stress-related disorders (pp. 1-18). IntechOpen.

Baig, H., Manchanda, R. K., & Nayak, C. (2009). Essential hypertension (CCRH Clinical Research Studies; series II). Central Council for Research in Homoeopathy.

Bhadoria, A. S., Kasar, P. K., Toppo, N. A., Bhadoria, P., Pradhan, S., & Kabirpanthi, V. (2014). Prevalence of hypertension and associated cardiovascular risk factors in Central India. Journal of Family and Community Medicine, 21(1), 29-38. https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8229.128766

Borde-Perry, W. C., Campbell, A., Wofford, M. R., Wegienka, G., Smith, D. W., & Wyatt, S. B. (2002). The association between hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors in young adult African Americans. Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 4(1), 17-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-6175.2002.00502.x

Borteyrou, X., Bruchon-Schweitzer, M., & Spielberger, C. D. (2008). Une adaptation française du STAXI-2, inventaire de colère-trait et de colère-état de CD Spielberger. L'Encéphale, 34(3), 249-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2007.06.002

Brosschot, J. F., Gerin, W., & Thayer, J. F. (2006). The perseverative cognition hypothesis: A review of worry, prolonged stress-related physiological activation, and health. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 60(2), 113-124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.06.074

Brotman, D. J., Bakris, G. L., & Townsend, R. R. (2003). The JNC 7 Hypertension Guidelines. JAMA, 290(10), 1312-1312. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.10.1312

Coulter, C. R. (1986). Portraits of homeopathic medicines: Psychophysical analyses of selected constitutional types. North Atlantic Books.

Cuffee, Y., Ogedegbe, C., Williams, N. J., Ogedegbe, G., & Schoenthaler, A. (2014). Psychosocial risk factors for hypertension: An update of the literature. Current Hypertension Reports, 16, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-014-0483-3

Dean, M. E., Coulter, M. K., Fisher, P., Jobst, K. A., & Walach, H. (2007). Reporting data on homeopathic treatments (RedHoT): A supplement to CONSORT. Homeopathy, 96(1), 42-45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.homp.2006.11.003

DeStefano, A. L., Gavras, H., Heard-Costa, N., Bursztyn, M., Manolis, A. J., Steffen, L. M., ... & Baldwin, C. T. (2001). Maternal component in the familial aggregation of hypertension. Clinical Genetics, 60(1), 13-21. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-0004.2001.600103.x

Di Blasi, Z., Harkness, E., Ernst, E., Georgiou, A., & Kleijnen, J. (2001). Influence of context effects on health outcomes: A systematic review. The Lancet, 357(9258), 757-762. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04169-6

Fagard, R., Brguljan, J., Staessen, J., Thijs, L., Derom, C., Thomis, M., & Vlietinck, R. (1995). Heritability of conventional and ambulatory blood pressures: A study in twins. Hypertension, 26(6), 919-924. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.26.6.919

Fisher, J. P., Young, C. N., & Fadel, P. J. (2009). Central sympathetic overactivity: Maladies and mechanisms. Autonomic Neuroscience, 148(1-2), 5-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2009.02.003

Friedman, R., Schwartz, J. E., Schnall, P. L., Landsbergis, P. A., Pieper, C., Gerin, W., & Pickering, T. G. (2001). Psychological variables in hypertension: Relationship to casual or ambulatory blood pressure in men. Psychosomatic Medicine, 63(1), 19-31. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200101000-00003

Fuentes, R. M., Notkola, I. L., Shemeikka, S., Tuomilehto, J., & Nissinen, A. (2000). Familial aggregation of blood pressure: A population-based family study in eastern Finland. Journal of Human Hypertension, 14(7), 441-445. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1001058

Gamboa, M., Herazo-Beltrán, Y., Hernández, E. V., García, E., García, K., Vásquez, M. J., ... & García-Puello, F. (2021). The impact of different types of shift work on blood pressure and hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(13), 6738. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18136738

Gerin, W., Davidson, K. W., Christenfeld, N. J., Goyal, T., & Schwartz, J. E. (2006). The role of angry rumination and distraction in blood pressure recovery from emotional arousal. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68(1), 64-72. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000195747.12404.aa

Gerin, W., Pickering, T. G., Glynn, L., Christenfeld, N., Schwartz, A., Carroll, D., & Davidson, K. (2002). The role of emotional regulation in the development of hypertension. International Congress Series, 1241, 165-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0531-5131(02)00497-7

Hahnemann, S. (1996). Organon of the medical art (6th ed.; J. Künzli, A. Naude, & P. Pendleton, Trans.). Birdcage Books. (Original work published 1810)

Hartog, C. S. (2009). Elements of effective communication—Rediscoveries from homeopathy. Patient Education and Counseling, 77(2), 172-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.021

Haynes, S. (1980). The relationship of psychosocial factors to coronary heart disease in the Framingham Study. III. Eight-year incidence of coronary heart disease. American Journal of Epidemiology, 111(1), 37-58. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112873

Haynes, S. G., Feinleib, M., & Kannel, W. B. (1980). Women, work and coronary heart disease: Prospective findings from the Framingham heart study. American Journal of Public Health, 70(2), 133-141. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.70.2.133

Hyland, M. E. (2005). A tale of two therapies: Psychotherapy and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and the human effect. Clinical Medicine, 5(4), 361-367. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.5-4-361

Javadi, F., Zargham-Boroujeni, A., & Molavi, H. (1998). Evaluating the relationship between blood pressure and frequency, intensity and style of anger expression in home and workplace of female nurses [Master's thesis]. Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Jorgensen, R. S., Johnson, B. T., Kolodziej, M. E., & Schreer, G. E. (1996). Elevated blood pressure and personality: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 120(2), 293-320. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.120.2.293

Kearney, P. M., Whelton, M., Reynolds, K., Muntner, P., Whelton, P. K., & He, J. (2005). Global burden of hypertension: Analysis of worldwide data. The Lancet, 365(9455), 217-223. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17741-1

Kjeldsen, S., Lund-Johansen, P., & Nilsson, P. M. (2014). Updated national and international hypertension guidelines: A review of current recommendations. Drugs, 74, 2033-2051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-014-0306-5

Knight, R. G., Chisholm, B. J., Paulin, J. M., & Waal-Manning, H. J. (1987). Self‐reported anger intensity and blood pressure. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 26(1), 65-66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1987.tb00728.x

Landsbergis, P. A., Schnall, P. L., Pickering, T. G., Warren, K., & Schwartz, J. E. (1994). Association between ambulatory blood pressure and alternative formulations of job strain. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 20(5), 349-363. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.1386

Lascaux-Lefebvre, V., Ruidavets, J. B., Arveiler, D., Amouyel, P., Haas, B., Cottel, D., ... & Ferrières, J. (1999). Influence of parental history of hypertension on blood pressure. Journal of Human Hypertension, 13(9), 631-636. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1000892

Light, K. C. (2001). Hypertension and the reactivity hypothesis: The next generation. Psychosomatic Medicine, 63(5), 744-746. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200109000-00006

Luft, F. C. (2001). Twins in cardiovascular genetic research. Hypertension, 37(2), 350-356. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.37.2.350

Mann, S. J. (2000). The mind/body link in essential hypertension: Time for a new paradigm. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 6(2), 39-45.

Manuck, S. B., Kasprowicz, A. L., & Muldoon, M. F. (1990). Behaviorally-evoked cardiovascular reactivity and hypertension: Conceptual issues and potential associations. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 12(1), 17-29. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm1201_4

Mercer, S. W. (2005). Practitioner empathy, patient enablement and health outcomes of patients attending the Glasgow Homeopathic Hospital: A retrospective and prospective comparison. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift, 155(21-22), 498-501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10354-005-0230-4

Mills, P. J., Dimsdale, J. E., Nelesen, R. A., & Dillon, E. (1996). Psychologic characteristics associated with acute myocardial infarction. Psychosomatic Medicine, 58(4), 379-382. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-198907000-00013

Moerman, D. E., & Jonas, W. B. (2002). Deconstructing the placebo effect and finding the meaning response. Annals of Internal Medicine, 136(6), 471-476. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-136-6-200203190-00011

Muldoon, M. F., Terrell, D. F., Bunker, C. H., & Manuck, S. B. (1993). Family history studies in hypertension research: Review of the literature. American Journal of Hypertension, 6(1), 76-88. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/6.1.76

Ohira, T., Peacock, J. M., Iso, H., Chambless, L. E., Rosamond, W. D., & Folsom, A. R. (2008). Longitudinal association of serum carotenoids and tocopherols with hostility: The CARDIA Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 167(1), 42-50. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwm249

Pickering, T. G., & Gerin, W. (1990). Cardiovascular reactivity in the laboratory and the role of behavioral factors in hypertension: A critical review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 12(1), 3-16. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm1201_2

Player, M. S., King, D. E., Mainous III, A. G., & Geesey, M. E. (2007). Psychosocial factors and progression from prehypertension to hypertension or coronary heart disease. Annals of Family Medicine, 5(5), 403-411. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.738

Ruiz, P. (2000). Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry (7th ed., Vol. 1). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Rutledge, T., & Hogan, B. E. (2002). A quantitative review of prospective evidence linking psychological factors with hypertension development. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(5), 758-766. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PSY.0000031578.42041.1C

Sacks, F. M., Svetkey, L. P., Vollmer, W. M., Appel, L. J., Bray, G. A., Harsha, D., ... & Lin, P. H. (2001). Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. New England Journal of Medicine, 344(1), 3-10. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200101043440101

Sorensen, G., Jacobs, D. R., Pirie, P., Folsom, A., Luepker, R., & Gillum, R. (1985). Sex differences in the relationship between work and health: The Minnesota Heart Survey. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 26(4), 379-394. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136658

Spielberger, C. D. (1999). STAXI-2: State-trait anger expression inventory-2. Psychological Assessment Resources.

Spielberger, C. D., Jacobs, G., Russell, S., & Crane, R. S. (2013). Assessment of anger: The state-trait anger scale. In Advances in personality assessment (Vol. 2, pp. 161-189). Routledge.

Stamler, R., Stamler, J., Riedlinger, W. F., Algera, G., & Roberts, R. H. (1979). Family (parental) history and prevalence of hypertension: Results of a nationwide screening program. JAMA, 241(1), 43-46. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1979.03290270025016

Suls, J., Wan, C. K., & Costa Jr, P. T. (1995). Relationship of trait anger to resting blood pressure: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 14(5), 444-456. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.14.5.444

Thompson, T. D. B., Weiss, M., & Hammes, M. (2006). Homeopathy—What are the active ingredients? An exploratory study using the UK Medical Research Council's framework for the evaluation of complex interventions. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 6(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-6-37

Tozawa, M., Iseki, K., Iseki, C., Kinjo, K., Ikemiya, Y., & Takishita, S. (2001). Family history of hypertension and blood pressure in a screened cohort. Hypertension Research, 24(2), 93-98. https://doi.org/10.1291/hypres.24.93

Vasan, R. S., Beiser, A., Seshadri, S., Larson, M. G., Kannel, W. B., D'Agostino, R. B., & Levy, D. (2002). Residual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA, 287(8), 1003-1010. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.8.1003

Wada, K., Tamakoshi, K., Tsunekawa, T., Otsuka, R., Zhang, H., Murata, C., ... & Toyoshima, H. (2006). Association between parental histories of hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidemia and the clustering of these disorders in offspring. Preventive Medicine, 42(5), 358-363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.01.012

Walach, H. (2003). Placebo and placebo effects—A concise review. Focus on Alternative and Complementary Therapies, 8(2), 178-187. https://doi.org/10.1211/fact.8.2.0005

Wang, N. Y., Young, J. H., Meoni, L. A., Ford, D. E., Erlinger, T. P., & Klag, M. J. (2008). Blood pressure change and risk of hypertension associated with parental hypertension: The Johns Hopkins Precursors Study. Archives of Internal Medicine, 168(6), 643-648. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.168.6.643

Webb, M. S., Smyth, K. A., Yarandi, H. N., & McCorkle, R. (2001). Hypertension in African American women: Influence of anger expression style. American Journal of Hypertension, 14(4S), 261A. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-7061(01)01845-4

Williams, J. E., Paton, C. C., Siegler, I. C., Eigenbrodt, M. L., Nieto, F. J., & Tyroler, H. A. (2002). The association between trait anger and incident stroke risk: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Stroke, 33(1), 13-20. https://doi.org/10.1161/hs0102.101625

Corresponding Author: Leena S. Bagadia, MD, PhD, CCMP, PGDMLE

Visiting Professor, Forensic Medicine & Toxicology

Smt. C.M.P. Homoeopathic Medical College, Mumbai, India

Email: leenabagadia@gmail.com

All Tables Included:

Table 1: Complete baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

Table 2: Primary STAXI-2 outcomes with effect sizes

Table 3: Secondary blood pressure outcomes

Table 4: Medication requirement changes

Tables 5-6: Family history sub-analyses for both genders

Table 7: Homoeopathic remedies prescribed with outcomes

Table 8: Correlation analysis

Table 9: Cost-effectiveness analysis

Table – 10 Analysis of Therapeutic Components